Model constructed by Bell company in Jan 1897 according to sketch in Bell's Mar 1876 telephone patent

(in preparation patent infringement suit against Dowd/Western Electric)

Everson in his book, says it worked.

Quick

summary of the case for telephone patent fraud

Telephone

Gambit by Seth Shulman (2008)

Heart of the Bell

story

Smoking gun

that Bell lied

Case for Bell

How

much telephone engineering did Bell actually do?

Did

Bell Steal the telephone from Gray?

Bell's lawyers

are slimeballs

My

Amazon review of 'Telephone Gambit'

Comment

on my Amazon review by Edwin Grosvenor --- Editor in chief of American

Heritage Magazine

Bell's

& Gray's 's variable resistance transmitter sketches

Bell's lab notebooks

Bell's

'telephone patent', #174,465

Bell

telephone invention time line -- 1876 to 1880

This essay is a review of Bell's role in the invention of the telephone covering both the engineering and patent aspects. I read three books covering this topic, which is pretty much the complete book literature, including a new (2008) book by Seth Shulman ('Telephone Gambit'). It was Shulman's excellent book that triggered my interest in this topic. I also dug around in the primary source material: reading through Bell's 'telephone patent' (#174,465) and looking through his lab notebooks (now online).

Introduction

I had long

been aware that there was a lot of controversy as to whether Bell really

should get credit for inventing the telephone. I remembered hearing (from

somewhere) that Bell's and Gray's patents had arrived at about the same

time at the patent office and that modern telephones looked more like Gray's

than Bell's. The telephone 'invention story' long peddled by AT&T and

widely quoted is this:

By a "remarkable coincidence" two inventors, Alexander Graham Bell and Elisha Gray, filed for a patent on the telephone on the same day (Feb 14, 1876). The patent was awarded to Bell because his patent application arrived at the patent office first just a few hours before Gray's.A review of the facts in a new book 'The Telephone Gambit' and in several other books shows that this AT&T story is largely self serving baloney. The real telephone patent story, as opposed to the engineering story, is basically one of crooked lawyers (Bell's) and bribed public (patent) officials combined with incompetent lawyers (Gray's).

Quick

summary of the case for telephone patent fraud

For from being

a coincidence the evidence is overwhelming that Bell's lawyers somehow

(maybe from someone in the patent office) got word that Bell's rival Elisha

Gray lawyers had just hand delivered a patent caveat to the patent office.

So to beat him out, they rushed to the patent office with a Bell's patent

application, which they had been sitting on three weeks waiting for it

to be filed in England, and demanding that it be special handled and immediately

be forwarded to the examiners office, which it was.

Bell's lawyers then called in favors from the examiner, who was both a friend of one of Bell's lawyers and owed him money, and got from him a series of favorable rulings (all a matter of public record):

a) Ruling that Bell's application had come in first (probably not true). This screwed Gray since a patent application trumped a patent caveat. (The patent office had no reliable means of tracking when during the day a patent applications arrived, so this could have been fought if Gray's lawyer had been competent and/or Gray had pushed it.)

b) Ruling that the requirement for an operating model was waived in this case. Pretty important as Bell up to this time had never got his telephone to really work, meaning it could transmit sounds, but not intelligible speech.

c) Bell's patent was approved by the examiner and the patent issued in the incredibly short time of three weeks!

The circumstantial case, as reviewed by the recent Shulman book (Telephone Gambit), is very strong that information about the Gray's confidential caveat, both its content and details of its filing, which were of course known to the examiner, made its way to Bell's lawyers.

a ) It helped Bell's lawyers make the case that Bell's application had priority.

b) It (very likely) helped Bell to make his first operating telephone. Bell did this just three days after returning from Washington by changing to a new (liquid variable resistance) transmitter design that was nearly identical to what Gray had described in his caveat.

c) The examiner may have even have allowed Bell's patent application to have been removed and altered to include material substantially identical to the contents of Gray's caveat. There's no doubt that material similar to the caveat (describing how to build a variable resistance liquid transmitter) was added to Bell application after it had been written, because the original Bell's hand written application survives and its shows this material written vertically in the in the margin.

New information that Shulman discovered in 2007 that is a further nail in the case. He found that the sketch that Bell made in his engineering notebook of his first operating telephone transmitter is nearly identical to the sketch Gray had drawn a few weeks earlier for his caveat.

Telephone

Gambit by Seth Shulman (2008)

I just finished

reading a new (2008) book on the invention of the telephone, called the

Telephone Gambit (by Seth Shulman), that has brought me up to speed and

interested me to know more. So I followed up by reading Everson's (an engineer)

2000 book, "The Telephone Patent Conspiracy of 1897" and Baker's (a patent

lawyer) 2000 book, "The Gray Matter, The forgotten story of the telephone."

The author of the Telephone Gambit has looked carefully at Bell's lab notebooks,

which (only!) after about a century (in 1975) were released by the Bell

family and only since 1999 have been readily available, and makes a good

case that hanky-panky was involved at the patent office by the lawyers

and examiners of Bell's 'telephone' patent, and very likely by Bell himself.

Doing my own research, I got a list of Bell's telephone patents and have

been reading them.

'Telephone

Gambit' by Seth Shulman, 2008

'The

Telephone Patent Conspiracy of 1897' by A. Edward Everson

(an engineer) 2000

'The

Gray Matter, The Forgotten Story of the Telephone' by Burton

H. Baker

(a patent lawyer), 2000

Interestingly the telephone grew out of work on multiplex telegraphs. This is what Bell was working on. It was the subject of Bell's first patent in 1875. Bell's second patent (early 1876) is now known as his 'telephone' patent and sometimes alleged to be the most financially valuable patent ever issued. However, when you read it you find that its focus too was on a method to multiplex the telegraph. The telephone section in the 'telephone' patent being little more than an add-on extension.

The telephone add-on was just a conceptual scheme in a figure that showed two electromagnets with variable gaps hooked together. Cones were pointed at plates that were parts of the gaps, the idea being that if air pressure modulated the plate in the gap of one electromagnet, then it would modulated the current in the second electromagnet and move its gap plate in the same way. At the time the patent was filed (Feb 14, 1876) it seems likely (book is not clear on this point) that Bell had even tried to build it, but it's certainly true that if he had tried to build it, it wasn't working.

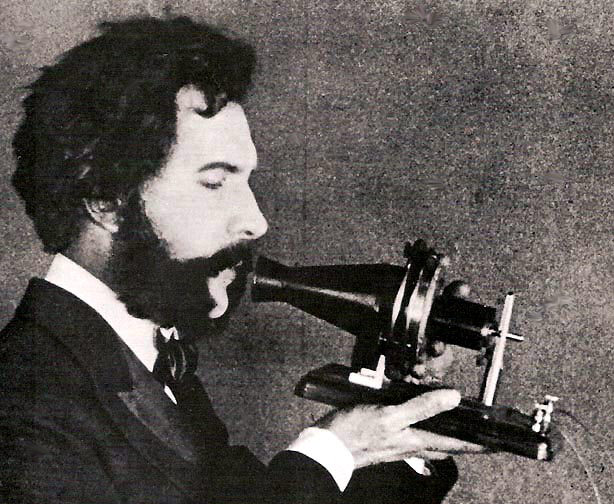

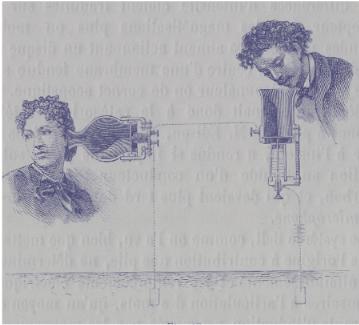

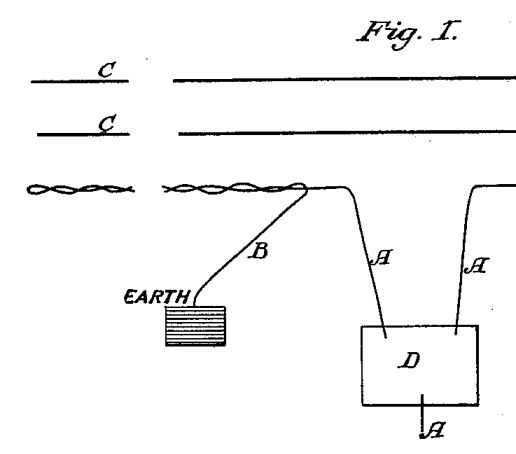

Here is a model

of a combo transmitter/receiver built to Bell's 1876 patent sketch (not

by Bell and three years later). It does in fact look just like the sketch

in the patent. Everson say in his book that it worked, meaning it did transmit

speech. ( I would take this claim with a grain of salt if it was not publically

demonstrated when it was built, because it was built by the Telephone company

as part of their patent defense, so it had to work.)

.

Heart of the

Bell story

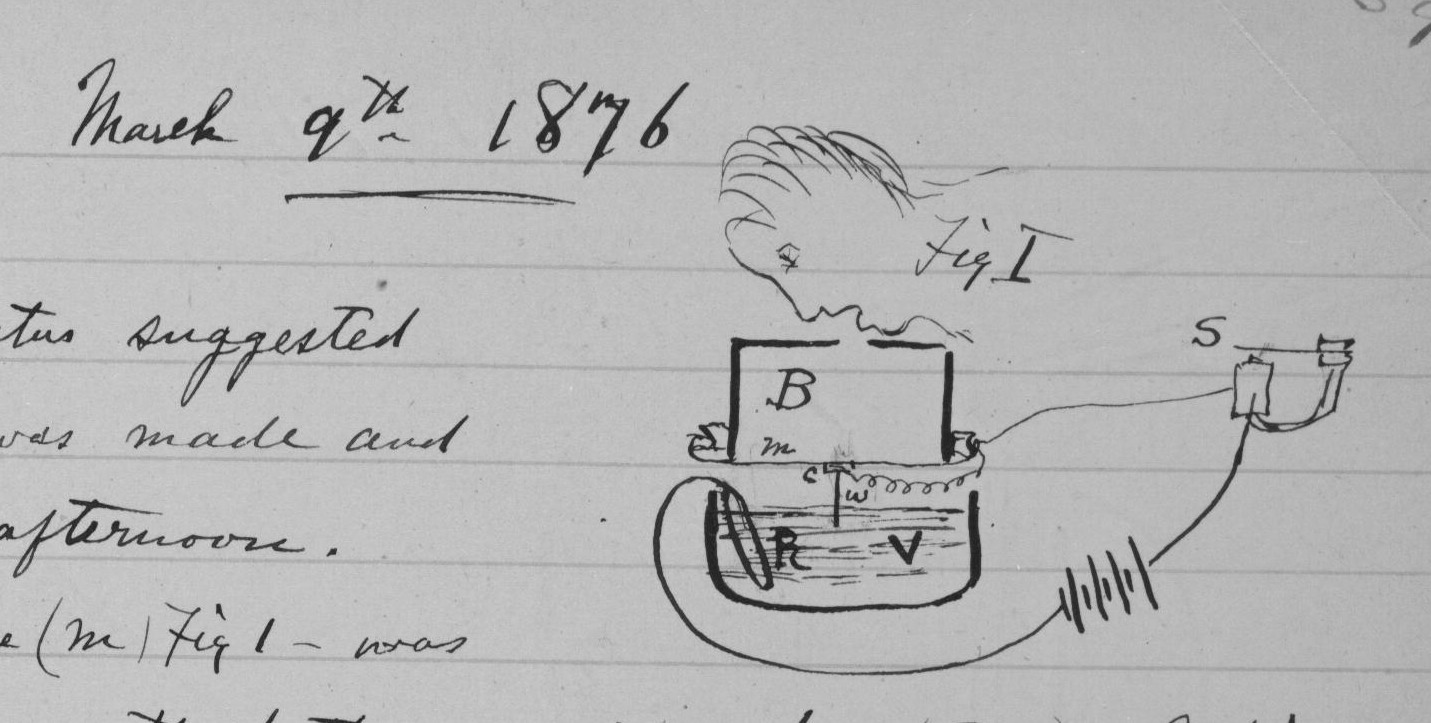

The heart

of the Telephone Gambit story is that almost immediately after Bell returns

from Washington with the patent in hand, his notebooks show him trying

an entirely new type of transmitter. He sketches it in his notetbook just

two

days after returning to Boston and the very next day (3/10/76) he succeeds

in sending and receiving speech ("Watson come here"). The new type of transmitter

is a variable resistance type made with a metal needle (connected to a

cone) rising and falling in water. This transmitter is clearly shown in

the sketch of Gray's 'caveat' that he filed with the patent office the

very

same day as Bell filed his patent application! Shulman is struck by

the fact that the 3/9/76 sketch in Bell's notebook looks almost exactly

the same as the sketch in Gray's caveat, filed 2/14/76 and supposely to

be kept secret for a year by the patent office. Therein hangs the tale.

Developing the magnetic transmitter

Very soon

(5-6 weeks) after his successful experiment with the liquid transmitter,

Bell stops working on it (very telling says the Gambit author!) and goes

to work on the magnetic telephone idea he sketched in his patent. And in

a few months it's working. He demos it in May 25, 1876 at MIT and a month

later (6/25/76) at the world's fair in Philadelephia before Lord Kelvin,

Elisha Gray, and many others using his magnetic transmitter. All are very

impressed, but it barely works, very faint and only some words are understandable

(distance 500 feet). Also the test is somewhat rigged because Bell's speaks

a well known Hamlet speech -- To be or not to be.

My comment --- Bell is trying to develop a variable reluctance transmit and receive device at a time when no one really had a good understanding of the magnetics involved. In addition there's the tricky issues of what material to use as a membrane, how to tension it, and how to couple it to the magnetics while still allowing it to move freely. And he has been working on this prototype for only a month or two before his spring 1876 demos at MIT and the world's fair. OK, it barely works, but still it impresses. It's a very early prototype, which is how he introduces it at the fair.With a few months more work on his magnetic devices it works better. By Oct he is able to do a sucessful two mile bi-directional test over a dedicated telegraph line, and in Feb 1977 a paid public demo from Boston to Salem (18 miles). In Jan 1877 he files a second telephone patent on an improved telephone with metal replacing a stretched material for the membrane, a new way to couple to the magnetics, and a PM replacing the electromagnet. Also this design is much more detailed, it looks like a product.

The Bell Telephone company goes into production with an electromagnetic transmitter and uses it for about two years (1877 and 1878) (Presumably this is Bell's design, but I have been unable to confirm this.) In 1878 Bell Telephone is competing with Western Electric, and starts losing customers to them because they from the start have used the better performing (louder) Edison's varible resistance carbon transmitter. In the beginning of 1879 Bell Telephone switches too to a carbon variable resistance transmitter.

Bottom line on magnetic transmitter

Unless someone

at Bell Telephone (was there any other designer beside Watson?) improved

his telephone design, it looks like Bell did in fact develop an electromagnetic

transmitter and receiver that evolved from his March 1876 patent sketch

and that worked well enough to be used by Bell Telephone commercially for

two years. Bell would have done this work in during the last seven months1876,

resulting in the design of his 2nd telephone patent, and possibly the first

six months of 1877, after which he takes a powder (year+ honeymoon). Shulman

says after he leaves on his honeymoon in mid 1877 he never really has anything

to do with the Bell Telephone company again, except testifiy for them in

patent cases, but I find this not to be true.

Bell as consultant (1878-1880)

Bell files half

a dozen telephone patents in the next two-three years, including one from

England six months into his honeymoon. Some are a little off the wall,

like his six inch balloon carbon transmitter, but several are detailed

exchange related engineering patents. And one ('twisted pair' patent, #220,791,

Oct 1879) is a major engineering contribution to the telephone engineering

(telephone signals are carried on twisted pairs to this day). These indicate

(to me) that even if Bell was not 'employed' by Bell Telephone, he at least

(at times) worked closely with them, because for several years he contributed

patents as a (in modern terms) 'consulting engineer'. This would be similar

to Gray who worked independently yet contributed patents to his former

company Western Electric.

Smoking gun

that Bell lied

For me the

smoking gun that Bell lied is this --- Bell claimed he added the seven

paragraph section on variable resistance transmitter (which three years

later will turn out to be a critical telephone component) on Jan 12, 1876

just before mailing it to his patent lawyers. Over the next few days he

makes several copies, one of which is to be filed for an English patent,

personally delivering a copy to Brown on 1/25/76, who sails for England

the next day. When Brown's copy is found (no reference given by Shulman

!! and I cannot find it), it turns out not to include the seven

paragraphs on variable resistance, which in a surviving draft (presumably

in Bell's handwriting) are written in the margin.

This is virtually proof positive that Bell did not add the variable resistance text when he said he did, it had to have been added later. And a very strong circumstantial case points to it being added after someone got a look, or hint, as to what was in Gray's caveat filing of 2/24/76. Conclusion -- Bell is a lying sonofabitch. (How does Shulman view this?)

Case for Bell

However, as

I see it there is a (remote) chance that Bell was telling the truth about

adding the variable resistance stuff at the last minute to the US filing..

The argument would be this:

If you read it (like I have), you find the 3/76, so-called 'telephone' patent, is primarily a multiplex telegraph patent with the telephone being an extension. The telephone described is nothing more than back to back (slightly modified) morse sounders, which it is claimed can (possibly) transmit vocal sounds. The text (& related claim) written into the margin about a variable resistance transmitter, is thus an extension of an extension. It is another, and more complex way, to transmit vocal sounds. It is possible that Bell upon reflection considered the latter to be really secondary and not that important (more complex since it required a separate transmitter and receiver and less practical since it uses a liquid), so he left it out of the copy prepared for British filing.I see a Gray mysteryIt's also possible (but unprovable ) that he had in the back of his mind doing a real, more comprehensive, telephone patent later when he got something to work. He might have just thrown in what ideas he had on the telephone into his 3/76 multiplex telegraph filing, because he was able to argue that the telephone worked in much the same way (using current 'undulations') as his multiplex telegraph.

More mysteries

Shulman (doesn't

necessarily say this, but he) leaves the impression that Bell come back

to Boston and having learned about the liquid transmitter the first

thing he does is build one and try it. (And only three days back from Washington

he has it working!) But this is not what the notebooks show. It's only

on the 2nd back in the lab that he begins to work on the liquid transmitter.

The first day (to be checked!!) looks much of his previous work.

Bell invents the telephone

So if Gray

didn't try, then it's fair to say that Bell invents the telephone.

He conceives of a magnetic approach early, patents it, and then with a

few months work perfects it enough to get customers and start the commercial

telephone business. It's only after two years of commercial use, that his

magnetic transmitter is replaced by an improved design.

And surprise, surprise, either by good luck, or more likely by scheming and fraud, it turns out that Bell's first telephone patent had a claim and text covering the principle of operation of a variable resistance transmitter too. (Thanks Elisha Gray, the future monopoy status of the Bell Telephone is assured!)

How

much telephone engineering did Bell actually do?

I think

a more interesting question than 'Who invented the telephone', is

'How much did Bell really contribute to bringing the telephone from being

a lab curiosity to a practical device, in other words how much did he contribute

to telephone engineering?' A few well dated Alex Bell milestones can be

placed in context with the known development of the telephone business

in the USA.

In March 1876 Bell first transmits understandable speech using a liquid transmitter. Not only is the liquid transmitter (probably) going to be hard to make practical, but Shulman makes a convincing case that Bell doesn't want to use it because he stole the idea from Gray and he needs (for several reasons) to keep this quiet. Also he thinks he has another way that might work, but which needs a lot of work. It's the all electromagnetic approach that he sketched briefly in his Mar 1877 (multiple telegraph) patent. If he can make it work, it has several (potential) advantages: it's his idea, it's patented, and being all electromagnetic it's likely to be more practical and easier to manufacturer than a liquid telephone.

In fact in a couple of months he gets his electromagnetic approach to work, not very well, but it does work well enough to transmit speech where at least some words can be understood. In May, June 1876 he gives demos to crowds of it at MIT and the world's fair. It looks like he spends the rest of 1876 working on an improved and more practical design that can be put into production. For example he replaces the unreliable parchment membrane with a metal membrane and switches over to a PM obviating the need for batteries.

The result of this six months of labor in the second half of 1876 is the combo transmitter/receiver telephone that he files for a patent on in Jan 1877. It seems likely that this is the model that went into production in early 1877 and began to be used by private customers in summer of 1877. Most or all of the engineering work on the first telephone exchange, which started up in Jan 1878, was probably done by others at Bell Telephone, since by summer of 1877 Bell is gone. He leaves for 15 months in Europe on his honeymoon, and he never returns to work for the company that bears his name.

Given this history I wonder when the engineering team at Bell Telephone began to be assembled. Is even the one production model that he probably (?) designed all his? Bell is the only name on the Jan 1877 patent that covers this design, and it must have gone into production in early 1877, or spring 1877 latest, so it's probably all or mostly his design. This is a picture of Bell with what is probably the first production telephone of the Bell company:

Alex Bell (age 29 in 1876) probably holding the first

production telephone, his electromagnetic

combo transmitter/receiver, described in patent 186,787

(issued 1/30/77).

Probably put into production in early 1877. (Wikipedia)

So how good was this phone? Well, a lot of people looked at it, and said, at least metaphorically, I can do better than this piece of crap.

Edison files a patent in Aug 1877 for an improved transmitter that has a mica membrane, a notch in the acoustic path to reduce overpressure of consonants, and a carbon variable resistance microphone that puts out much more power than Bell's electromagnetic microphone. Six months later (early 1878) Western Electric starts to use Edison's microphone in their telephones and in about another year Bell Telephone switches over too after they acquire the patent rights to it in a deal with Western Electric.

Did

Bell Steal the telephone from Gray?

Here's Wikipedia's

summary (in Elisha Gray and Alexander Bell telephone controversy). This

is accurate and I agree with the conclusion.

Although Bell was accused, and is still accused, of stealing the telephone from Gray, Bell used Gray's water transmitter design only as a proof of concept scientific experiment to prove to his own satisfaction that clear human voice sounds could be electrically transmitted. After that, Bell focused on improving the electromagnetic telephone. Because Bell's electromagnetic telephone did not use Gray's invention in public demonstrations or commercial use, Bell did not steal Gray's invention.Bell's lawyers are slimeballs

After meeting with his lawyers (Polk and Bailey) in Washington in Mar 1875, Bell writes his parents that his lawyers 'know' he is far ahead of his rival Gray on the harmonic telegraph and consequently have broken up his telegraph filing into three application, two of which they expect will not interfere (overlap) with Gray's and one of which will. But as of March 1875 the content of Gray's two telegraph patent applications, which are sitting in the patent office, are still secret. Gray's harmonic telegraph patents, filed in Jan 1875, will not issue and become public until July 1875.

This is near proof that Bell's lawyers were obtaining confidential information about Gray's patent applications and are were using it (unethically and illegally) to benefit their client Bell and his influential backer Hubbard at the expense of Elisha Gray. And its not hard to guess that their source at the patent office is inspector Wilbur, friend and debtor to Bailey, who handles all the telegraph patents, and who later in life affirmed that this is what he did.

Note the fact that Bell seem OK with using information from unissued patents indicates that he is (as of Mar 1875) either very unknowledgeable about patents or else he thinks like his slimball lawyers.

Bell's file copy

Bell's file

copy is the version of the March 1876 (first telephone patent) now

at the Library of Congress that was obtained from Bell papers and is thought

to be his handwritten copy for the Feb 14, 1876 filing. A facsimile copy

is included in the Baker's appendix (pA71, version F). Baker's book also

includes the (recovered) Brown version, which while printed, has additions

and deletions noted changes by use of caps and brackets.

When Shulman (and virtually all recent telephone authors and the 1880 court cases too) talk about the (clearly later) additions to this file copy that were written vertically in the margin, they almost always just just talk about the variable resistance material. Since this material was missing from the Brown version, it's a small jump to conclude that the variable resistance material (& claim) must have been added to Bell's application either just before or (illegally) after its Feb 14, 1876 filing, after Bell's attorneys (somehow) learned about the wire in water variable resistance transmitter in Gray's (confidential) caveat, which was also filed Feb 14, 1876 and which is known to have been written in the three days prior to its filing.

Nice neat story, but it' too neat. A close review of the documents shows some facts that just don't fit the story very well.

a) The variable resistance 'wire in liquid' is only one of four

different margin

changes in Bell's file copy.

b) Brown's (recovered) copy had deletions not in the original (unmodified)

Bell's

file copy making it likely that it is an earlier draft, and (I argue) probably

not the version taken to England.

Margin changes in Bell's file copy

Below are

the four margin changes to Bell's file copy all of which are missing from

Brown's version. Note of the four changes listed only #3 is close to the

contents of Gray's caveat. Undulating currents can be produced three ways

(below in order given):

1) Side to side vibrations in the plates of a battery, which changes its

internal resistance

2) External resistance changes, such as a wire vibrating in mercury or

other liquid

3) Up and down vibrations of the plates of a battery, which vary its "power"

("power" probably means 'voltage' in modern terms)

On a separate

page where there is list of four advantages of undulating currents the

list is expanded to five. The list of advantages appears to be rather random,

so it's interesting that a new 5th advantage was just not inserted and

labeled 5th, instead the old 4th advantage is relabeled 5th and

4) A new 4th advantage is added in the margin vertically.

To me these four margin changes appear to be a general (last minute) revision not just the insertion of an item stolen from Gray.

Why Brown's recovered version appears to be an early

draft

The (five)

claims in Bell's file copy begin a new page and are clearly written in

a different hand. This would be consistent with Bell's lawyers writing

the claims and giving him a copy of his records. (The word "alternately"

in the fourth (variable resistance) claim is crossed out and changed to

'gradually'. This change is known to have been part of a few (supposedly)

minor 'clarifications' that the patent office (for some strange reason)

allowed (by amendment on Feb 29, 1876) about two weeks after the

patent was filed.)

Brown's copy has been upgraded with major deletions and additions. The biggest being all the claims have been rewritten: first set crossed out and a new set written under them. (Of course this change is consistent with having been done at the NYC meeting just before sailing.)

* In Brown's copy there is crossed out sentence followed by a replacement sentence:

--- [Undulating current of electricity may be produced in many ways than that described, but all the methods depend for effect upon the vibration or motion of bodies capable of inductive action.].

replced by this:

--- There are many [other] ways of producting undulating current of electicity, but all of them depend for effect upon the vibration or motion of bodies capable of inductive action.

The unmodified Bell file copy says:

--- There are many ways of producting undulating current of electicity, but all of them depend for effect upon the vibration or motion of bodies capable of inductive action.

Bell's file copy is modified by omitting 'but all of them depend' with the word 'dependent' (This change required for consistency with variable resistance transmitters.) The modifed version makes it to the issued patent.

--- There are many ways of producting undulating current of electicity, depend for effect upon the vibration or motion of bodies capable of inductive action.

'Recovered' Brown version

Smoking gun?

Bell's patent

application had material added in the margin (oriented vertical) that described

a liquid, variable resistance transmitter that was substantially identical

to material contained in Gray's confidential caveat. Bell testified that

he added the variable resistance material in Boston at the last minute

before mailing it to his lawyers. A week or so later Bell wrote his fiancee

that he and a copyist he had hired were busy making (handwritten) copies

of it (plus several other applications): one for the patent office, one

for

Brown (to use for an English filing), and one for himself.

Yet a few years later, when the Brown version showed up as evidence in a court case, it was found to be missing the variable resistance text and claim. Is this not a 'smoking gun' that Bell lied, greatly strengthening the case that the variable resistance material was obtained from Gray's caveat and later interpolated into Bell's patent? Certainly the attackers in the 1880's court cases thought so, and so do nearly all the modern books on the telephone patent fraud.

After reading Shulman's book, I thought so too. The Brown version missing the variable resistance material certainly seemed to be the smoking gun that Bell's application, when it was sworn to, could not have contained the variable resistance material. But now I'm not so sure. When you look closely at the Brown version and the known circumstances about it, things don't add up.

Consider...

* The differences

between the Brown version and published patent is not just the missing

the variable resistance material. In the harmonic telegraph section Brown

version lists four advantages, the final patent contains five. The Brown

version is full of crossed out text and small wording differences. The

Brown version is clearly, without question, an earlier draft of

Bell's patent application.

* In days when travel mean taking the train Bell travels from Boston and xxxx comes up from Washington to meet with Brown in New York a day or two before he sails for England to discuss the English filing for a patent and Brown financial stake in this enterprise.

To me it's (almost) inconceivable that after traveling to New York just for this meeting that the patent application they give Brown, the one that will be used for an English patent filing, would be an earlier draft with stuff missing. And Brown isn't going to ask, 'This is the final version, right, the same as is being filed in Washington?' Even if they skimped on the copying and it was an earlier draft, why at dinner would not Bell update it by adding in the missing stuff? After all, we know he wasn't opposed to writing in the margin!

* There has been an earlier meeting with Brown in Canada (Brown's Canadian and Bell spent time at his parents house in Canada) about De 29, 1875 to establish the business relationship with Brown (he agreed to pay Bell a monthly fee to support his work for some patent rights). Bell testified that he had been drafting his patent application for months before its Feb 14 filing. So isn't it likely (very likely) that around the time when the business relationship with Brown was established (end of 1875) that Bell gave Brown a copy of the application as it then stood, or maybe even an outdated version? After all the (potential) patent is what Brown was 'buying' from Bell.

* What is now called the 'Brown version' was only gotten back from Brown (by Watson) in Canada two years after he sailed to England.

Bottom line

With all the

principals traveling to NYC to meet with Brown before he sailed, I argue

he must at that time been given an application that if not clean was

at least was up to date, consistent with what Bell wrote in his letter

to Mabel. I also argue that because Brown's business relationship with

the potential patent had formed a month or so earlier it's not unreasonable

that Brown had been given a draft of the application at that time. Two

years later when he is asked to produce the Bell application for the court

he produces the earlier rather than the later version.

Who knows, maybe Brown didn't know the two versions were different. Maybe the version he took to England (to be rewitten for an English filing) he never got back or brought back. Maybe when he looked into his files this is all he had. Who knows?

If this is the case, then the fact that the recovered Brown version is missing the variable resistance tranmitter section is off the table, it tells us nothing about when the variable resistance material was entered into the appplication.

Bell's explanation

In a deposition

taken 16 years later Bell said the variable resistance material was not

included in the copy Brown took to England by "by some oversight" and "by

some accident the matter was overlooked". This is not an explanation.

It is a best a lame excuse. Baker calls it incredible. How could no one

notice that Brown's copy had one less claim that clean copy awaiting US

filing?

Comparing Brown version to Bell file copy

When the Brown

verson is discussed, the discussion is virtually always limited to the

'famous' missing seven lines. This is the only text in the patent that

discussing variable resistance and which in the handwritten Bell file copy

were written vertically in the margin. But a much more detailed comparision

can be made using the reference material in the appendix of Baker's book.

Both versions have additions and deletions, so it's useful not only to compare the baseline documents, but look in detail at the whats added and deleted. There are enough changes that we may be able to figure out how to order the doucments. Baker in his book (p117) says Bell's file copy in its original handwritten form "conformed almost exactly" to the version given to Brown for filing in England (really the Brown version recovered two years later). I don't agree. I see evidence that the Brown version is an earlier draft.

Arguments

* Bell's file

copy had two large insertions written vertically on different pages in

the margin. One, of course, is the famous section that includes variable

resistance and wire in a liquid. The other is fifth advantage of undulating

currents. But not just the variable resistance text is missing in Brown,

the fifth advantage of undulating current is missing too. This is

significant, because the argument that Bells patent is changed after filing

(while Bell is in Boston) with material learned from Gray's caveat on variable

resistance, must now also include and unrelated change, the addition of

a fifth advantage for undulating currents.

Arguments con

Wouldn't Bell,

or possibly his father in law (if he knew), have remember giving Brown

an earlier version? When asked by the court (a few years later) why the

variable resistance material was missing from Brown's copy, why did Bell

not mentioned? (It could possibly be because it would put Bell in

conflict with Brown, who claimed this was the application that he had gotten

just prior to sailing, althogh he never provided a date.)

Baker's book talks about the court record showing that small changes were allowed in Bell's application on Feb 29, 1876, which is about two weeks after it was filed. Very strange. However, I have not seen anywhere what the Feb 29 changes were. I suppose it's possible that the addition of a fifth advantage (mentioned above), which was missing from Brown copy, might have been one of the Feb 29 changes.

It's only ohms law

To me an engineer

it's could very well be that the variable resistance material was added

to his application, just as he testified, at the last minute before he

mailed his application to his lawyers. He's written up what he has done

in the lab, but in a patent you try to be as broad as possible to cover

all bases. His patent focues on what he calls 'undulating current', meaning

currents that vary continuously as opposed to on/off as in a normal

telegraph. He asks himself is there any other way to get current to continuously

vary. Sure there is. Just connect a battery to a resistor and a current

flows determined by one of the simplest rules in electronics, ohms law

(i = V/R).

So (I am supposing

he realizes) that another way to cause "undulation" in the current is smooth

continuous variation in either the battery voltage or the resistance.

-------------------------------------------------------------------

My

Amazon review of Telephone Gambit (5/1/08)

Review title:

Shulman nails it

"This is an

excellent book. I bought it hoping it would give me (a retired electrical

engineer with more than a dozen patents) some understanding of the telephone's

genesis, which I knew to be a complicated tale with claims that Bell didn't

deserve the credit. Frankly I was hoping for a good story and Shulman delivers.

He lays out the twists and turns of this story in a remarkably clear narrative,

but this is not just another retelling of the telephone story.

Shulman started working on this book only because he made a startling discovery in Bell's lab notebooks. He found that Bell's sketch of his first (functioning) telephone transmitter was nearly identical to a sketch drawn by Elisha Gray in his (supposedly) secret filing with patent office a month earlier. And even more suspiciously Bell had drawn the sketch in his notebook just days after returning from Washington where he had conferred with his patent lawyers and the patent examiner. Shulman has researched in depth if, how, who, and why fraud was committed in the patenting of the telephone, with close attention to how things were later explained in court depositions and testimony. The picture Shulman draws is very convincing that major hanky panky (fraud) occurred in Bell's patenting of the telephone. Shulman lays out the case that Bell had a strong motive (love first, money second) to go along with the fraud, even though he many not have initiated it, and as Shulman argues, his shame and need to conceal his use of Gray's idea nicely explains many of his later actions that have always been puzzling. It all hangs together very well. The case for patent fraud is overwhelming, and Shulman draws the appropriate conclusions.

So is Bell essentially just a crook who stole Gray's design and deserves no credit? Well it's easy to jump to this conclusion after reading this book, but there's another side to this story. For starters read the Wikipedia article: 'Elisha Gray and Alexander Bell Telephone Controversy'. It explains, based on facts fully consistent with Shulman's book, why (in their opinion) Bell did not steal Gray's invention. My opinion, after reading Bell's patents, researching the design of the first US telephones, and doing some reading of Bell's notebooks (available online from the Library of Congress) is that while it appears that Bell stole Gray's idea in the legal sense (via patent fraud), he didn't steal it in the engineering sense.

The undisputed fact is that Bell and his partners started the telephone business in the US with a Bell designed electromagnetic telephone. By modern standards it was primitive (weak, distorted, and only good for 10-20 miles or so), and it lasted in the marketplace less than two years before being replaced by a telephone much closer to modern phones with a variable resistance carbon transmitter. On the other hand the Bell design was simple (it was a combo receiver/transmitter), easy to manufacture, and most importantly it worked well enough so that thousands of people put down their money to buy or rent one.

Note Bell's electromagnetic telephone design was indisputably his own design. It had nothing to do with the famous seven (disputed) paragraphs written in the patent margin, which described the concept of a variable resistance transmitter. The variable resistance transmitter required another year of development work (by Edison, Blake and others) and was not introduced into the market (by Western Electric) until about a year after Bell's phone business began.

So did Bell 'invent the telephone? The early phone (and associated telephone exchanges) were the work of Bell, Edison, Blake, and others, but Bell by using a simple, low performance design of his own was able to get to market a year ahead of his competitors and get the US telephone business off the ground. So if there is to be a 'single' inventor, Bell (by virtue of his being first) is the inventor of the telephone."

Comment

on my Amazon review by Edwin Grosvenor

Edwin Grosvenor

added a comment (below) to my Amazon review on 11/25/14. The name Edwin

Grosvenor sounded familar and a little research showed he is the Editor-in-Chief

of American Heritage magazine and the author of an 1997 book an Alexander

Graham Bell.

Edwin Grosvenor says: (11/25/14)A rereading of my 2008 essay shows that I too found at the time a lot Shulman's judgements to be questionable.

"You might want to look at the Wikipedia essay on the Bell-Gray controversy again -- a lot has been added. Bell's drawings are consistent over a span of three years, long before Gray submitted his, and there was a similar liquid transmitter in Bell's patent for a fax machine which was granted by the PTO the year before. Shulman didn't really know much about the history of the telephone, and has done a real disservice."

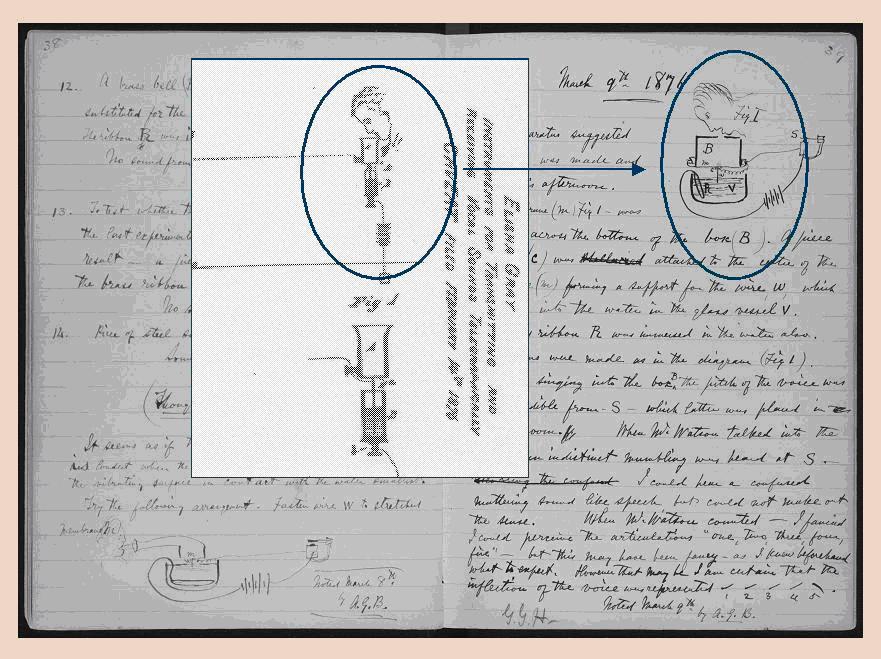

The sketch below appears to be (or purports to be) Gray's original because it's hand dated 2/11/1876, which is the Friday before the Mon 2/14/1876 filing. It's included in Baker's 2000 telephone book 'The Gray Matter'. This is important because Baker is sort of a Gray specialist. He doesn't appear to reference the source of this figure. However, he had access to Gray's archives at Antioch college, and he had a natural sympathy to Gray because he worked as a patent lawyer at Whirlpool corp whose chairman was Gray's grandson and stories of Gray and the telephone had long circulated around the company. (Note, according to Shulman, Bell's notebook's were never brought forward for any court case and only in recent years have they become publicly accessible. So if the similarity to Bell's sketch is because this sketch is a fake, it has to be a late 20th century fake.)

The dating is consistent with the history that Gray wrote out the caveat (in Washington) just a few days before it's filing. It's not hard to believe that the caveat figure (see below) could have been drawn from this sketch (by a draftsman employed by the patent firm) because the essential features are the same. Also there is confirming evidence in the many minor (or from an engineering point of view unimportant) details that are the same, for example, the shape of the receiver sound chamber, the rim flare on the liquid beaker, the location of the liquid beaker terminal centered below it, and the label 'Line' on the wire between the transmitter and receiver.

(apparently) Gray's original sketch for his caveat

Hand dated 2/11/1876 (Fri before Mon 2/14/1876 caveat

filing)

Compare this to a close up of Bell's notebook sketch that I captured from the official archives.

Bell's notebook sketch of his his liquid transmitter

used for first transmission of articulated speech

Dated 3/9//1876 only two days after returning from

Washington

(My crop of from Library of Congress image of double

Bell notebook pages)

Bell claims

(under oath) he has not seen Gray's caveat (or Gray's original sketch?),

but notice the similarities.

* Similar speaking heads

-- both include speaking heads

-- heads are men

-- heads pointed left (& nearly horizontal)

-- mouths open

-- heads have same look (Bell's little less detailed)

* Same location of elements

-- transmitter on left and receiver on right

-- battery between base of liquid chamber and receiver

-- speaking chamber has prominent terminal

(located on its bottom right)

Of course not all these similarities are independent or too important. For example, with a liquid transmitter, it's going to be necessary to bend over to speak into it. Once the transmitter is put on the left and the receiver on the right (with the line between them), the most natural location for the transmitter terminal is on the right of the liquid container (and at its bottom). The circuit would work with the battery anywhere in the series path, but its most natural location is in the ground path of the transmitter (rather than in series with the line), and this is where both sketches have it (Bell's is a little ambiguous).

Below is another sketch of Gray's design. I screen captured this from Bruce's 1990 book on Bell (as displayed on Amazon). Bruce labels it 'Diagram for Elisa Gray's caveat'. Where did this come from? I doubt this was drawn by Gray because clearly more effort was put into drawing the men than the apparatus. It just doesn't look like an engineering or patent sketch. It's out of balance and too artistic. My guess is that it was redrawn by an artist for some publication.

Gray's caveat sketch for liquid transmitter from Bruce's

Bell book

Here's a more realistic drawing of Gray design, which I found online.

Sketch from Gray's caveat

Is this a redraw (in patent style) of Gray's dated

2/11/1876 original by a draftsman on Gray's legal team?

Note it is drawn reversed (speaker now on right) from

Gray's 2/11/1876 sketch.

----------------------------------

In spite of the near certainty of patent fraud it's undisputed

(I think) that the first US commercial telephones (exclusively in 1877

and in competition with Western Electric in 1878) used a simple electromagnetic

design of Bell's. It was clearly his design, totally different from Gray's.

It had been sketched (but not yet reduced to practice) in his famous telephone

patent draft notarized in Jan 1876, the sketch is in all drafts of Bell's

patent including the Brown version. Note Bell's electromagnetic telephone

design has nothing to do with the famous seven (disputed) paragraphs written

in the margin. The seven paragraphs were about the next step in telephone

transmitter design, the variable resistance transmitter, which Western

Electric began using in early 1878 and Bell Telephone switched to in early

1879.

So did Bell

'invent the telephone? My answer is yes. Bell's simple electromagnetic

design (combo receiver/transmitter) was weak transmitting, but it worked

up to 10-20 miles and was good enough to get the telephone business

in the

---------------------------------

The case laid out

in the book is so strong that it's tempting to just conclude that Bell

was a crook and doesn't deserve any credit. Unfortunately Shulman almost

temps you to so conclude by stopping the story a tad too early. By not

discussing the design of the first commercial US telephones, he leaves

out information crucial to evaluating Bell's contribution, information

which puts Bell in a better light.

Bell's lab notebooks

Wow!

No wonder these notebooks are so neat, they are'nt real (contemporaneous)

lab notebooks these are cleaned up copies of lab notes. Page 7 is

signed "Copied Feb 21, 1876" and the purports to describe experiments

run six to nine months earlier (June to Oct 1875).

The timing

is interesting. This cleaned up notebook is prepared in the 10 days between

the filing of Bell's telephone patent (& interference with Gray discovered)

and the time he leaves for Washington.

-----------------------------------------------

Bell's lab

notebooks are available online from the Library of Congress. They are quite

readable as Bell's handwriting is very good, and there were grayscale scanned

at 300 dpi. They are almost too readable. Why are the sketches so formal?

Everything is labeled patent style. Next to the battery symbol he sometimes

writes "battery". Clearly Bell is not just writing for himself.

I assume the formality and detail is because this is what the patent lawyers wanted if they had to establish "first to invent". The irony is that even though the telephone patent was perhaps the most litigated patent in history these notebooks were never offered up and their content never disclosed to anyone (according to Shulman). The "first to invent" in Bell vs Gray was decided on the basis of notary dates of their respective patent filings.

Bell worked in the lab on his multiplex telegraph & telephone for no more than two and half years: 1875, 1876 and first half of 1877, when he got married and essentially retired from telephone work. Link below is for notebook Oct 1875 to April 1876. This covers the three months before he filed his 'telephone' patent and includes the first famous 'phone call' of Mar 10, 1876.

Page 19 he returns from Washington (3/7/76), page 21 has sketch of the man talking into a liquid transmitter (3/9/76) that Shulman noticed was almost the same as the sketch in Gray's caveat, page 22 has "Watson come here", the first time he transmits and receives understandable speech (3/10/76).

http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/ampage?collId=magbell&fileName=253/25300201/bellpage.db&recNum=20

Mysteries

The implication

in Shulman's book is that he comes home from Washington carrying the liquid

transmitter idea acquired (somehow) from Gray's caveat. But Bell's notebook

shows that when he restarts his lab work after the trip he does not

start right away working on the liquid transmitter. He sketches the idea

for the transmitter only on the 2nd day back, and it's built and working

by the third day back

Receiver

Most of the

discussion of early telephone design talks about the transmitter, but it

appears to me that the receiver needed a lot of work too. An electromagnetic

(coil, movable gap) structure can in fact work as both a transmitter and

receiver, and one of Bell's early telephones worked this way. In Bell summer

1876 World's fair demo, equipment that just barely works, his receiver

is not the same as his transmitter even though the transmitter is electromagnetic.

The receiver looks very crude. The movable plate looks to be just lying

on the magnet (he need to get a very small gap) and apparently you put

your ear right on the plate.

In his lab notebooks Bell shows that his 'receiver', i.e. where the sound comes out, is almost always shown (& labeled) as a Morse sounder. He usually sketches it as coil wound around a square metal loop with a pivoted piece on the top. It looks a lot like a standard sounder except he doesn't show any stops making the movable piece free to move (a little) up and down.

He may have had a couple of different types. Sometimes when he is trying to detect musical tones (from a tuning fork), he says he puts the movable piece of the sounder directly against his ear. But when trying to listen for speech he uses sounder where the movable piece in the electromagnetic flux path is a metal membrane that can vibrate, and coupled to the membrane is a tube that focuses the sound to the ear. He has quite a detailed, pencil drawn sketch of his membrane sounder in his notebook.

A standard Morse sounder is shown below. It had became the standard telegraph 'receiver' (clicker) around 1850. The vertical cylinders are the electromagnet coil(s), which are wired to the telegraph line. There is a gap in the magnetic flux path of the electromagnets connected to a pivoting horizontal rod. When the electromagnet is driven by current from the telegraph line, it pulls down on the pivoted rod narrowing the gap. It looks all metallic, so a current pulse probably made a double click, one at start (down) and one at stop (up), but it wouldn't be hard with a little felt pad to muffle one of the clicks.

Morse sounder -- standard telegraph 'receiver'

Current in electromagnet (vert cylinder) pulls pivoted

(hor) brass arm down causing click

Transmitter design

Here are the

key design features:

Membrane --- you need a material that moves with high amplitude on low pressure, can be tensioned, and will hold tension (impervious to temp, moisture, time). There are also issues with its self resonance. Parchment may suffice by a quick test, but it's not going to work for a commercial phone. Edison says animal products like hides are also not reliable, so he chooses mica.

membrane material

Bell used parchment, then metal

Edison says mica best

Coupling to membrane

How to couple the

membrane to the variable resistance material, or in the case of the electromagnetic

transmitter to vary the reluctance. This is tricky. The moving membrane

needs to maintain contact with the 'read out' material, but it must still

be free to easily move.

Variable resistance or reluctance

Is the 'read out'

variable resistance or variable reluctance. In variable resistance there

can be power gain, meaning there is more power in the electrical signals

that was picked up from the sound wave with the extra power coming from

a local battery. This might also be true too in a well designed

variable reluctance structure using an electromagnetic powered by a battery.

Electromagnet or PM

Bell in his

commercial phones replaced the electromagnet with a PM (permanent magnet).

With a PM there is no external source of power, so all the electrical power

must

come

from power picked up from the vocal input. No gain. However, this was (apparently)

good enough for at least a few miles. I have yet to find out how far spread

out were the customers of the first New Haven switchboard. Bell and Watson

in early 1877 publicly demonstrated fairly reliable comprehension was possible

at a distance of 18 miles, but I have yet to see what type of equipment

they used for this test..

Comprehension

Early telephones

worked much better with vocal sounds than consonants (Bell, Edison, and

newspaper accounts all note this). Edison says this is because consonants

were overpressuring the transmitter membrane. He introduces a notch or

opening in his acoustic path which he says helps a lot. Too resonant a

membrane gave voice a ringy character. Edison liked mica over metal, because

he said it is layered and thus non-resonant (meaning well damped).

Bell's

'telephone patent', #174,465 (March 7, 1876)

References

below to 'patent' refer to Bell's March 7, 1876 (issued) patent, #174,465,

Improvements

in Telegraphy (filed 2/14/1876), commonly referred to as

the 'telephone patent'. Reading this patent I find its primary focus is

on a frequency multiplex telegraph that uses current "undulations" (sinewaves)

as opposed to "make and break" operation. The transmission of noise, musical

tones, wind, noise or vocal sounds, which also use "current undulations",

is a secondary usage of the equipment ("other uses"). This is Bell's second

patent

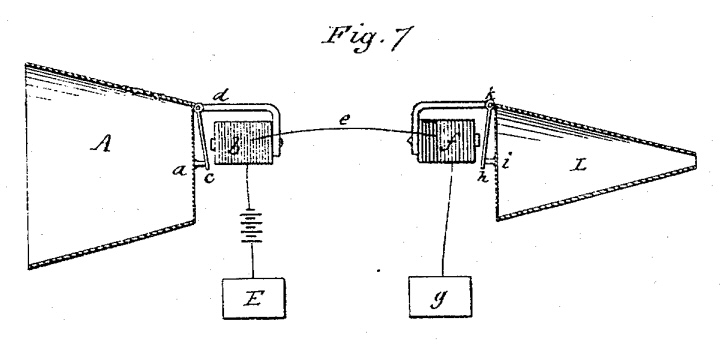

However the 'telephone' patent does include a sketch (fig 7, below) of two electromagnetic transmitter/receivers connected back to back, which is essentially what Bell first introduces to the market. More important legally its claims include producing undulations (in current) by "increasing or diminishing the resistance of the circuit", which is what the carbon microphone will eventually do (claim 4). And claim 5 includes "method of, and apparatus for (fig 7), transmitting vocal or other sounds telegraphically".

two electromagnetic transmitter/receivers back-to-back

"The undulatory current passing through the electromagnet

(f) influences its armature (h)

to copy the motion of the armature (c) A similar sound

to that uttered into (cone) A

is then heard to proceed from (cone) L"

Fig 7 from Bell (first) 'telephone patent' #174,465

(issued 3/7/1876)

Bell's first patent (161,739) filed about a year earlier (April 6, 1875) was a a totally impractical multiplex telegraph that is really a crude fax machine. It required messages written in ink on metal to be 'scanned' by being pulled under a matrix of close wires with paper similarly being pulled under a matrix of receivers for an inked image to be written. At this time Hubbard is already one of his backer (one of the assignees). The impracticality of this 'fax' patent must have been obvious to Hubbard.

Bell

telephone invention time line -- 1876 to 1880

Unfortunately

Shulman does not give a time line in his book the Telephone Gambit, but

paging through his book, and reading Bell's patents, I've pulled one together.

(I put most of this togther before I found Wikipedia's telephone time line.)

1876 -- First telephone prototypes are developed (by

Bell)

1/12/76 Bell finishes

up handwritten draft of patent and mails it to his Washington patent lawyers.

The transmitter uses a stretched material for a membrane (This type

of membrane, says Edison, is unreliable, because it loses tension when

it absorbs moisture from breath.) The membrane couples to an electromagnet

that pushes on it.

This draft, which is preserved in the national archives, shows that what later turns out out to be a key section (seven paragraphs on variable resistance transmitter, such as a metal rod projecting into a liquid, and presumably the related 4th claim), is clearly a last minute addition, because it was written in the margin. Bell testifies he added it just before he mailed it on Jan 12, 1876, but much evidence says it may very well have been added (by someone) after Gray's caveat was filed Feb 14, 1876. If this is true, then Bell was a lying sonofabitch.1/20/76 Bell signs and has notarized a clean copy (presumably with drawn figures) that he has received back from his patent lawyers.

1/25/76 Bell hands a copy (that he and a paid copiest) has written out to Brown, who next day is sailing for England and is to file it with English patent office. (Bell is still, I think, is an English citizen at this time.)

A key point is that Brown's version of the patent application does not contain the seven paragraphs (on the liquid variable resistance transmitter) that Bell supposedly added to the application 1/12/76. Based on this it appears very, very likely that Bell lied (under oath) when he said the seven paragraphs were added 1/12/76.2/14/76 Bell's patent is filed (by his lawyers against his instructions!) and the same day Elisha Gray's telephone patent is filed (by him?). Gray's caveat is notarized also on this day (2/14/76), whereas Bell's was notarized three weeks earlier (1/20/76).

This difference in notary date is crucial, because who invented first is what counted to the patent office at this time. So if text about a variable resistance transmitter was in fact illegally slipped into Bells' patent application after its notary date (1/20/76), then it gets an earlier invention date than Gray's. This turns out to be crucial in several ways.2/24/76 Bell's interrupts his experiments and travels to Washington (on patent business).One, since it created an overlap, an interference in patent office jargon, between Bell's and Gray's filing, even if Bell didn't see Gray's caveat, he may have gotten a strong hint from the patent examiner as to what was in Gray's caveat, because Bell said the patent examiner pointed at the seven paragraphs and said the interference was here.

Gray's lawyer told him that he would lose a fight on the interference, because of Bell's (supposedly) earlier notary date, so Gray, an experienced inventor and patenter, dropped his caveat. (And he apparently never tried to build the liquid transmitter he described in the caveat.)

Why exactly does he go to Washington? Don't think Shulman addresses this, but presumably the patent interference has been discovered and he needs to talk over what to do with his patent lawyers and (future) father in law, investor, and big time Washington insider lawyer, Hubbard.6/76 Bell in Washington and discusses his patent with the patent examiner.Evenson argues that Bell's lawyer Polk inserted the seven pages on variable resistance (and revised the claims) just prior to Feb 14, 76 filing (attaching Bell's notarized signing page to the end of it). Bell then goes to Washington at Polk's request 10 days later to fix the draft version in Polk files, which is retained and is still extant, so that it match the filing. Bell writes the seven paragraphs on variable resistance in the margin. If true, of course this makes Bell fully complicit in the fraud. (This smells like it could just be a dirty little trick that patent lawyers like to pull on their fellow lawyers to get priority.)

The examiner it turns out is a friend, and even owes money to, one of Bell's patent lawyers. The examiner is a drunk too, and ten years later signs an affidavit that says he showed Gray' caveat to Bell at this time! Gray also tells the story that he ran into the patent examiner (Wilber) on the streets of NY years before the affidavit and the examiner told Gray that he was the inventor of the telephone.3/7/76 Bell arrives back in Boston from Washington. On the same day (three weeks after filing) his patent is issues as #174,465.

Patent is issued only three weeks after it is filed, Shulman who looked into this say this is not usual, but I find most of Bell's patents were issued within a month of filing.3/9/76 Bell draws a water type transmitter in his lab notebooks with a man's face talking into it.

This is only two days after he gets back from Washington, and there is a very strong similarity between Bell's notebook sketch and the sketch in Gray's caveat. Shulman, who has studied Bell's lab notebooks, says nothing like this liquid transmitter (and a face) has ever appeared in them before this date. Shulman was the first to notice the simularity of Bell's sketch to Gray's, and it's what set him off digging into Bell's telephone work. These two sketches are the genesis of Shulman's book.Shulman is certainly right about the similarity. It is striking. The same rectangular voice box, and even the angle of the head is almost the same. (Shulman notes that nowhere before in his notebooks has Bell drawn a head.) But it's even more interesting when you look at Gray's original sketch, see section 'Bell's & Gray's 's variable resistance transmitter sketches' (above).

3/10/76 Bell on this day is the first to operate a working telephone. It uses the water variable resistance transmitter he sketched the day before. Years later Watson, Bell's lab assistant, will write in his autobiography that the first use of the phone had been when Bell called him from the next room, saying "Watson come here, I want you". Historians like a pithy story, so they adopted it making it famous.

Key and undisputed fact --- Bell demonstrates a working telephone only after his patent is granted and only three days after he returns from Washington. It uses a brand new (to him) transmitter design that is not the transmitter he sketched in his patent but is just like the transmitter sketched by Gray in his 2/14/76 caveat filing.(end of April to early May) Bell's notebooks indicate that he stops work with the water variable resistance transmitter, and he begins working only on the electromagnetic concept that he had included in his patent.

5/22/76 Bell gives a talk at American Academy of Arts and Sciences (in Boston) about his phone and does a demo, but only music is transmited (how?) and played over the receiver for the audience. Shulman says he mentioned the liquid transmitter briefly, but focuses on the electromagnetic transmitter.

Date could be 5/10/76, both dates appear in Shulman's book. Note he is using equipment he must have thrown together very quickly, probably within a month or two.5/25/76 Bell gives a demo of speech transmission at MIT before a crowd.

First public demo of speech transmission. Local newspaper story on this demo says consonants were not very clear. (Bell also notes in his lab notebooks that consonants are hard to discern.)6/25/76 Big time demo at 1876 World's Fair in Philadelphia. Bell demos speech transmission (distance 500 feet) and also demos his duplex telegraph. Many famous experts are here including Lord Kelvin, who is a judge, and Gray, who sees Bell's demo.

The early prototype telephone demoed at the world's fair barely worked. Bell rigged the demo by giving a famous Hamlet speech, but even knowing what was coming only some phases could be made out. Still Kelvin and others were amazed at hearing speech over a telegraph.8/3/76 and 8/10/76 Wikipedia has first 'long distance' calls by Bell, 4 miles and 10 miles.Shulman argues that Bell used the electromagnetic transmitter here, though he had the (probably) better performing liquid transmitter with him, because it was important to Bell that he convince Gray that he had invented the telephone independently (and first). In this he succeeded, though a few years later Gray later become convinced that Bell had deceived him and stolen his transmitter design.

Gray at the world's fair demonstrates an octoplex telegraph, four message both ways simultaneously vs Bell's duplex (two message) demo.

From his home in Brantford Ontario to a local telegraph station over a wire strung up along the telegraph wire. Distance 4 miles. Later Brantford to Paris Ontario. Distance: ten miles. From Wikipedia's description of the equipment it seems very similar, or the same(?), as the June World's fair equipment.10/9/76 Successful two mile, bi-directional, test in Boston of improved equipment over a dedicated

(end of 1876) Hubbert offers to sell Bell's telephone technology to Western Electric (telegraph people) for $100,000. Answer no.

Western Electric's 'no' was considered by later business students to be one of the worst business decisions of all time. Western Electric soon (early 1878) goes into the telephone business in competition with Bell using patents from Gray, Edison, and others. But they are shut down (79 to 80) when they lose the Dowd patent infringement case.1877 -- Bell Telephone starts producing electro-magnetic telephones for use on private lines

1/15/77 Bell's files his 2nd telephone patent (his 5th patent, the other three are all telegraph patents). This is a product type patent with only (as I read it) sketchy info about the magnetic design, except that it does have a metal membrane and PM. Even in this patent the first use is telegraphic and the second usage is telephonic.

It looks like this could be a patent for equipment that they hoped to sell. In fact it looks a lot like the telephone (on Wikipedia) that shows Bell speaking into it dated 1876. This is a single device used as both transmitter and receiver, unlike the June 76 World's fair equipment which used separate devices. Patent issues in two weeks (#186,787) on 1/30/77.2/23/77 Bell does a speech demo for a paying crowd with improved equipment that uses (??) the electromagnetic transmitter from Boston to Salem. Distance 18 miles.

(Summer 1877) AT&T history says that by summer of 1877 the telephone "had become a business".

The implications of "had become a business" is probably that Bell's Jan 1877 patented telephone (or a modified version of it) was practical enough for general use and Bell Telephone had begun to manufacture them in the first half of 1877. In 1877 the telephone is used by customers only over dedicated lines, meaning you can't call anyone, except the person on the other end of your line. For example, a factory owner or doctor might run wires from his office to his home and buy the phones from Bell.July 1877 Bell gets married and takes off on a 15 month honeymoon to Europe.

So any further improvement of the telephone appear to the work of others, very likely engineers of Bell telephone. Well, my patent research says this may not be true. Bell files several practical telephone patents in the following two to three years, including one while on his honeymoon, and a very important patent #220,791 (issued Oct 1879) showing use of 'twisted pairs' for telephone lines. Twisted pair wiring is so effective at removing interference (& it has other advantages too) that to this day this is how telephones wiring is done.8/28/77 Edison files a patent (patent #203,015) for a variable resistance type transmitter that uses compressible carbon fibers, which will soon become the standard telephone transmitter.

Fig 1, Bell 'twisted pair' patent 220,791, issued Oct 1879

(telephone line is twisted with ground (lower). Lines C,C are interferring lines)Bell, says Shulman, played no role at all, technical or management, in the company that bears his name (Bell telephone) after summer of 1877 when he leaves on his honeymoon. He comes back a few times in years ahead only to give depositions and to testify in court cases where Bell is trying to shut down competitors, and then only under great pressure including from his wife. (Well he may not have been an employeee of Bell Telephone, but the patent record indicates he continued to work on the telephone, some ideas speculative, but others look to be in the mainstream of telephone engineering.)

Edison in his Aug 1877 patent on the carbon resistance transmitter for the telephone notes, as did Bell, that consonants are a problem. He explains the problem is that they overpressuring the membrane, and he introduces a notch in his speech cone which he says substantially solves the problem.Edison choses mica for his membrane claiming it has lots of advantages over materials previously used for membranes: it's not resonant, it doesn't stretch, it's impervious to the heat and moisture of breath, and it's very sensitive.

Early phones for many years are required to have a local battery to power the carbon microphone, and they also need a transformer (really an auto-transformer) in the phone to step up the low inpedance of the carbon microphone to match the impedance of the line. (Bell in a Jan 1880 patent filing notes that the battery and coil are standard in phones used on exchanges.)Oct 11, 1877 Thomas A. Watson, formerly Bell's assistant, files a patent application to add a call bell to the telephone.This reference discusses Edison's work on the telephone in 77 & 78 in some detail. It says Edison made 150 telephone sketches Jan to Aug 1877. And importantly that Edison continued working on the telephone after his Aug 1877 patent filing (into 1878) and changed over from plumbago to a carbon button.

Watson is now a telephone engineer and inventor. In this patent (#202,495) he says specifically that he is adding a call bell to the "magneto-electric" telephone Bell patented in Jan 1877. The sketch looks remarkably like a modern telephone call bel,l and it is rung with high voltage applied to the line.Dec 1877 Western Electric forms a telephone company (American Speaking Telephone Company) using the patents of Gray, Edison and others.

1878 -- Bell Telephone starts an exchange and Western Electric starts selling telephones with Edison's carbon transmitter

Jan 1878 First Bell telephone 'exchange' starts operation in New Haven Conn. This apparently is a central system, hence 'exchange', as opposed to dedicated private lines.

First published New Haven telephone directory, about a month after exchange starts in business, shows about 50 customers.Feb 9, 1878 Telephone product improvement patent (#201,488) filed by Bell. It's an improved magnetic structure (shaped "tubular" PM with the coil wound inside).

Shulman in hia book gave the distinct impression that Bell stopped work on the telephone when left on his honeymoon in July (or Aug) of 1977. But this patent, which looks like it may be a real improvment in the magnetic design of his combo receiver/transmitter ("telephone can be lifted to the mouth or ear, as required") was filed by Bell from England about six months into his honeymoon.April 1878 Western Electric sucessfully tests Edison's improved carbon transmitter.I supposed it's possible that this product improvement work was not done by Bell at all, but by someone else at Bell Telephone (like Watson), but for the good of the company they had the famous Bell file for the patent. (This would be, of course, illegal.)

Edison's new carbon button, variable resistance telephone is tested on a 90 mile line (New York and Philadelphia), and it tests out well with even whispers loud and distinct. It was this 'carbon button' design that Western Electric bought the rights to and started using in their phones.(thru summer 1878) Watson tries to develop variable resistance transmitter that doesn't infringe on Edison carbon transmitter patent, but has no success.

Sept 12, 1878 Dowd case begins. Bell Telephone files suit against (effectively) Western Electric claiming patent infringement.

Oct 1878 Bell telephone acquires rights to a carbon transmitter of Francis Blake

(Late 1878) Bell telephone is losing business to rival Western Electric because Western Electric telephones use the "much louder" Edison carbon transmitter.

Within a year of being formed Western Electric's American Speaking Telephone had installed 56,000 telephones in 55 cities. Bell Telephone is still using an electromagnetic design (Bell's design?)1879 -- Bell Telephone switches over to carbon transmitter and at end of year Western Electric exits telephone business

(Early months of 1879) Bell Telephone is near bankruptcy.

Wikipedia says Bell Telephone is now 'desperate' to get a transmitter to equal Edison's carbon transmitter, and only Francis Blake's invention of a carbon transmitter similar to Edison's saves the Bell company from extinction.(early 1879) Bell telephone begins using Blake's carbon transmitter.Details on Blake's transmitter here. According to this reference Blakes transmitter was widely used in US and throughout the world for 20 years. This reference also has this interesting little tidbit: 'Later introduction of a battery boosted Bell Telephone's electromagnetic transmitter performance a bit'.

This probably means the PM was changed to electromagnet, because then (I suspect) it was possible to design a variable reluctance electromagnetic transmitter to get some gain from a battery in much the same way as a variable resistance transmitter does. The implication of this is that if Bell himself did not do this work (there is no patent), then Bell's design may not have been used until the switchover to Blake's carbon transmitter.

Bell telephone and Western Electric are now both using carbon transmitters. The reign of the electromagnetic transmitter at Bell Telephone lasted about two years (77 and 78). The first year (1877) with probably relatively few private line customers and the second year (1878) a lot more since telephone exchanges begin to open. Western Electric (apparently) right from its start (in early 1878) uses Edison's carbon transmitter, which was developed mid 1877 to early 1878. (Western Electric paid Edison to work on the telephone.)July 1879 Bell testimoney in the Dowd (Western Electric) patent infringement case runs to 100 pages

7/17/79 Bell files a patent (#220,791) on using a "twisted pair" of wires to run telephone signals to avoid interference from current in adjacent wires. At the time the motivation was to avoid crosstalk between circuits, but later it would prove effective in preventing pickup of 60 hz hum from AC power wires.

This is important, because it turned out to be a key step in telephone engineering, and thus of great practical use. Telephone signals to this day are run on twisted pairs of wires. I don't know how much was known of twisted pairs in those day, but from reading the patent it appears that Bell may have been the first to 'discover' how immune twisted pairs are to outside interference.11/10/79 Western Electric makes a deal with Bell Telephone to give up the telephone business, sell their exchanges to Bell, and assign all their telephone patents to Bell.

Western Electric settles because they are sure they are going to lose the (Dowd) patent case. Bell is inclined to settle because it gets the rights to Edison's transmitter and an end of Western Electric's countersuit against Bell claiming infringement. Western Electric gets money (20% of telephone rentals for next 17 years).12/26/79 Bell files a patent (#250,704) for putting two "sound-conveying tubes" on a phone, one to hold to the ear and one to speak into.

This is a curious patent to file at the end of 1879. Bell Telephone had switched over to using a separate transmitter (carbon variable resistance) and receiver almost a year earlier (beginning of 79). This applies only to combo receiver/transmitter type phones, like Bell's electromagnetic, and is pretty trivial at that. Did Bell still have hopes for the combo type telephone, or does this indicate that at this time he was an outside inventor and not really up on telephone engineering?1880 -- Bell continues telephone work (as Bell Telephone consultant)

1/2/80 Bell files a patent (#228,507) (assigned to National Bell Telephone) on a very sensitive, variable resistance transmitter that has high resistance.

Curiously this telephone transmitter is a 6 inch toy balloon covered with a carbon film material (plumbago). Bell notes that the high resistance of this transmitter is an advantage because it would eliminate the need for a (troublesome) local battery and step up coil in each phone.3/13-16/80 Bell files two telephone patents (#238,833 & #230,168 ) three days apart, the first for a call bell and the second a shorting relay.

These are both are both very practical looking switchboard related patents. The first a complex bell design and line wiring to allow the central office to ring just one phone on the line. The shorting relay is to force customers to call the central office only by using the recommended push button (not taking the phone off the hook).8/28/80 Bell files his 'photophone' patent. This is (apparently) an attempt to send signals using light waves.These two patents indicate to me that Bell in early 1880 is closely connected to the engineering of the telephone network and is making real contributions.