Estate tax update

Getting

money out of IRA's without paying taxes

Money

can be withdrawn from IRA's without being taxed if it goes directly to

charity

PBS estate planning

guru (Ed Slott) on minimizing IRA taxes at death

IRA beneficiary vs Will

Beneficiaries

for non-shielded accounts

A Primer on Roth IRA

conversions

Standard

IRA vs Roth IRA Overview

Tips for Reducing Your

Estate

Charity

donations at death reduce taxable estate

Remove

life insurance proceeds from your estate

Comment

on life insurance tax avoidance risk

Charity

Options for Qualified assets --- At death

Charity

Options for Qualified assets --- Living

Estate Tax Rules

-- Federal

Loop

hole to reduce capital gains tax and pass more wealth to heirs

Gift Tax

Charity

remainder trust and access to university endowment investments

Donor Advised Funds

Keep

deductions in line with AGI (50%, 30%, 20% limits)

Is

the limit for appreciated securities 30% or 20%?

** Hidden

TurboTax 'trick' to get more value from very high charity contributions

of appreciated securities (3/15)

403(b) to IRA Rollover

** IRA

money to charity at death

* Charity

begins at age 71

Links to charity

financials

Notes on tax efficient ways to give money to charity. Funds remaining in IRA accounts at death are good candidates to leave to charity, because if left to heirs a substantial fraction of these funds will be lost to taxes. Also 'directed beneficiary' information for bypassing probate.

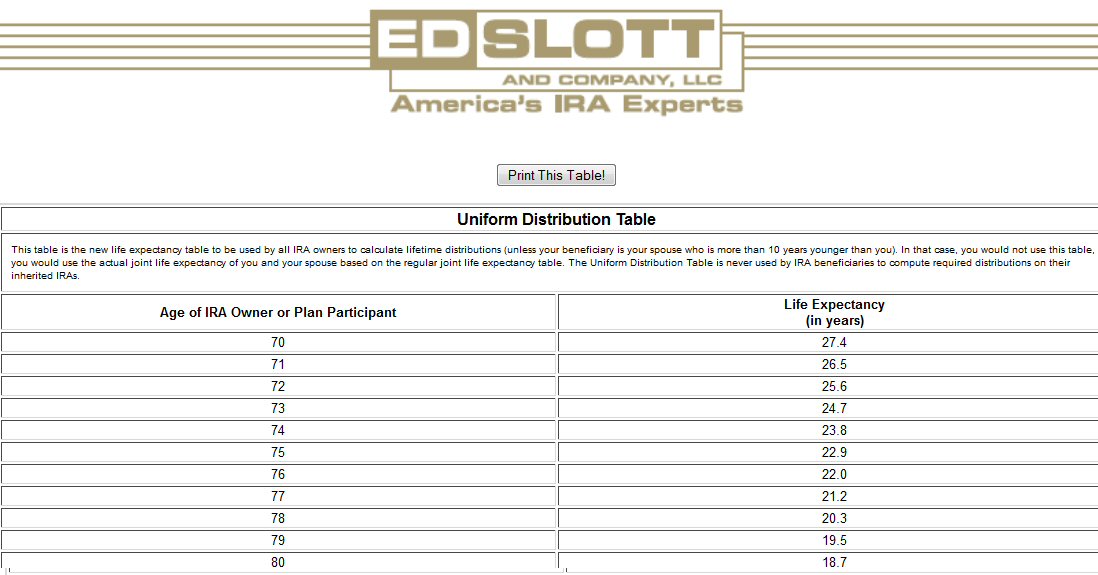

Minimum withdrawal update (12/29/08)

Congress has

now started to mess around with, and of course greatly complicate notes

Ed Slott, IRA 'minimum withdrawal' rules. These rules are important because

they control when IRA assets get taxed.

WSJ reports a bill and been passed and signed that suspends minimum IRA (& 401k) withdrawals for the years 2009 only. Now that IRA taxation is no longer a fixed compact, I suppose we need to plan on congress increasing IRA withdrawal rates in future whenever there's a need for more revenue.

Estate tax update (4/27/12)

(1/1/13) (3/4/16)

Hillary is

still just a candidate (3/4/16), but her 'soak the rich' tax proposals

include lowering the fed estate tax exemption from 5.45 million to 3.5

million and changing the tax rate from 40% to 45%. Here's a detailed

analysis of her tax proposals:

http://taxpolicycenter.org/UploadedPDF/2000638-an-analysis-of-hillary-clintons-tax-proposals.pdf

----------------------

Press is saying

(1/1/13) as part of end of year budget negiotions the fed estate starting

in 2013 and for indefinite future will be:

Fed 5.25 million exemption (per person), 40% (flat) rate above

The estate tax requires continual tracking as it is all over the place. As of 2012 the rates are:

Fed

5.12 million exemption, 35% (flat) rate above

Massachusetts 1.00 million exemption,

progressive rate

1st million 3.6% approx

2nd million 6.8% approx

3rd million 8.4% approx

4th million 10% approx

5th - 9th million rate rises about 1% per

million topping out

at 16% for 10th million and higher

Example

For a 4 million taxable (5 million estate) tax is 239k

(5.98% average)

For a 9 million taxable (10 million estate) tax is 787k

(8.74% average)

Under current law the federal estate tax exemption is scheduled to decrease to $1,000,000 on January 1, 2013 and the fed tax rate to increase from 35% to 55%!

(update 12/22/10)

The idiotic

(federal) estate tax yo-yo continues. The newly passed two year extension

of Bush tax cuts reinstates the estate tax in 2011 and 2012 with these

numbers: maximum rate of 35% with a $5 million exemption per person. (This

compares to 0% tax in 2010, and in 2009 a 45% maximum rate with $3.5

million exclusion.) The 35%/5 million rates sunset Dec 31, 2012. Beginning

in 2013, there will be a $1 million per person exclusion with a 55% estate

and gift tax rate unless further legislation is enacted.

(1/26/12, Fidelity)But don't forget state estate taxes, and Fidelity says all of them have an exception less than 5 million:

For 2012, both the estate tax and lifetime gift tax exemption is $5,120,000 per person and $10,240,000 per couple with a 35% top tax rate. Beginning in 2013, however, unless further legislation is enacted, the exemptions will drop to $1 million per person ($2 million per couple) and have an effective top tax rate of 55%.

-- States have their own estate taxes. Approximately 17 states plus the District of Columbia impose an estate tax. These state estate taxes are separate from the federal estate tax and they all have exemptions that are lower than the $5 million federal exemption.(12/4/09)

(10/23/08)

Prior to the election

and (really subject to change) --- "Obama's plan calls for keeping the

estate tax exclusion at $3.5 million (2009 level) permanently, as well

as for maintaining the 45 percent tax rate." (NYT) Current law has the

estate tax in 2011 returning to 2001 levels. This is an exclusion of only

$675,000 and a tax rate 55 percent, so if there is no legislation this

is where estate taxes are going.

Getting

money out of IRA's without paying taxes (12/06)

Normal withdrawals from IRA's (etc) are heavily taxed (at incremental earned

income tax rates), but congress has begun to provide some 'backdoor' tax-free

IRA withdrawals. Every new tax bill seems to open up another back door,

so it's important to keep up with the law. Here are those I am aware

of

1) At death any amount

of IRA money can go to a charity tax free

if the charity is

listed as the beneficiary of the account. This money is not counted

as

being part of your estate, so it may help with estate taxes too.

2) If over 70.5, 100k/yr can be transferred from an IRA

to a charity tax free

(Ended Dec 31, 2013. It had helped meet IRA Minimum Required Distribution

requirements,

but curiously & importantly excluded a 'Donor Advised Charity')

3) If over 55, 3.65k can be transferred (one time) from an IRA

to an HSA (Health

Saving Account). HSA is a shielded account, but withdrawals from

HSA's to pay medical cost are not taxed.(lots of restrictions)

4) A stretch IRA (promoted by IRA guru Ed Slott in his book Parlay Your

IRA into

a Family Fortune). If an IRA is properly set up and properly handled

at

death, the next generation beneficiaries of an IRA can 'stretch' it using

their much longer expected lifetimes to reduce the required minimum

payout to 3% or so a year. This can allow the IRA to grow for decades

more and greatly reduces the effective tax the beneficiaries have

to pay

on the inherited IRA money.

5) IRA RMD (Required Minimum Distributions) for 2009 has been reduced to

zero

by Worker, Retiree, and Employer Recovery Act of 2008.

(So much for simplification, now congress is messing with the basic

structure of IRA's!) This was supposedly a one time thing

to help the economy from 2008 financial crash.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------

(new) Transfer from IRA to

HSA (Health Saving Account)

Only before you sign up for Medicare, only if you have HDHP (high deductible

health plan), and only for a limited amount of money. If over 55,

3.65k can be transferred (one time) from an IRA to an HSA (Health Saving

Account). HSA is a shielded account, but withdrawals from HSA's to pay

medical cost are not taxed. (Wall St Journal)

HSAfinder.com4HSAUsers.com

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Money

can be withdrawn from IRA's without being taxed if it goes directly to

charity

Qualified

Charitable Distributions (9/25/15 update)

Qualified

Charitable Distributions were reinstated by congress for deductions in

2014 only in dec 2014 (with expiration 12/31/14)! It allowed up to 100k

direct transfer from shielded accounts, and this withdrawal can be used

to meet IRS minimum distribution requirements. A direct IRA to charity

contribution will not appear on your AGI (adjusted gross income). Tiaa

points out that this is an advantage for people living in states that do

not allow charitable deductions (like MA). Since I live in MA and need

to take minimum distributions, doing charity this way would save about

5% on MA taxes for the amount donated.

However, this provision is loaded with restrictions. A big kicker (same as previous years) is that the contribution cannot be made to donor advised fund, it must go directly to a public charity. Another big restriction Tiaa-Cref points out is 403(b) plans don't qualify, though they suggest a work around is to roll over funds from a 403(b) to an IRA, and then make the charitable contribution from the IRA. Qualified Charitable Distributions have not been reinstated for charity contributions made in 2015 as of Sept 25, 2015.

For 2015 one reference advises the following:

As of April 2015, the QCD rules have lapsed again. and there is no guarantee that Congress will reinstate them retroactive to the beginning of 2015. This same situation has presented a quandary over the last few years as taxpayers have had to wait until the end of the year to find out if their QCDs would reduce taxable income. So what’s a person to do in 2015?----------------------------If you plan to make substantial charitable donations in 2015 regardless of whether Congress renews the QCD rules or not, then there really is no good reason not to issue those donations directly from your IRA! The worst case scenario is that Congress fails to renew the exemption and you’re forced to account for the donations as itemized deductions (as though you had taken a distribution from your IRA and then written a separate check to the charity)…but if Congress does renew the tax break retroactively to the beginning of 2015, as they have done in the past, then you’ve potentially taken advantage of one of the best tax breaks available to retirees without having to wait until the last minute to make your donations. (However, this doesn't address the question of whether or not charitible contributions from an IRA still meet the minimum distributions requirements if congress doesn't act.)

I don't have any person experience with this provision. I was thinking I did in 2013, but when I checked my records my RMD from IRA was a cash withdrawal. I gave 50k to to my Fid donor advised charity in 2013, but this money did not come from an IRA account. It was appreciated securities that came from a taxable account. This of course that is the reason it did not show up on my income tax and increase the AGI (adjusted gross income). As long as the source of the money going to charity is from a taxable account, I doubt the 100k (or ANY) limit applies, after all you are giving away after-tax money.

Here's Ed Slott

Wednesday, August 13, 2014-----------------------

The provision for qualified charitable distributions (QCDs), which allows IRA and inherited IRA owners 70 1/2 or older to transfer portions of their accounts to qualifying charities tax-free while satisfying all or a portion of their RMDs (required minimum distributions), expired at the end of 2013. Although widely expected to be reinstated by Congress at some point there is no guarantee that will actually happen. That’s especially true since this is an election year.Each time Congress has brought back the QCD provision in the past, they have made it retroactive to the date it previously expired. As a result, assuming you had followed the rules for QCDs during the periods of time the provision was expired, your distributions eventually were treated as valid QCDs. While there is absolutely no guarantee that if Congress brings back the QCD provision again, it will once again do so retroactively, there’s more than a reasonable chance they’ll do so. At worst, you’ll have to claim the distribution as income on your return and claim the contribution to charity as an itemized deduction.

A direct IRA to charity 'transfer' (by IRA custodian) can be used to meet up to 100k of IRA RMD requirements in 2013. The procedure is to ask "IRA custodian to send the distribution directly to the charity, rather than funneling the money to charity yourself." But "IRA funds donated this way cannot be used for contributions to donor-advised funds. Subject to those constraints, the money can go to any organization to which you can make a gift that would qualify as a charitable deduction on your tax return." (from Forbes)

How useful is Charitable IRA rollover?

Just started

to think about this, but to first order I don't see any major (fed) advantage

here, nor did a Forbes article see any. Plus there's a lot of hassle and

gotches. The biggest one is that the money can't go to a donor advised

charity. That means each charity 'transfer' must be done separately probably

requiring calls and emails to both the charity and IRA provider. (However,

after this is done once, it may not be that hard 2nd time. I suspect there

are also gift thresholds here too.) Another big issue is this is IRA only.

It does not apply to 403(b) accounts (I confirmed this with a tel call

to Tiaa-Cref).

It does appear though that in states like MA with almost no deductions, that the portion of the IRA withdrawal going to charity this way avoids being taxed by the state (as income). In MA this would be a 5.25% savings.

1st order is a wash (fed)MA tax advantage

To a first order [donating to charity + itemized charity deduction] is from a tax viewpoint the same as using charitable IRA rollovers. In the first case the portion of the withdrawal that will go to charity is added to AGI and then subtracted off (dollar for dollar) to form taxable income, and in the second case of the charity rollover withdrawal the charity funds never appears as income with the result that taxable income is the exactly the same in both cases.For example, suppose total RMD [from IRA and 403(b)] is 85k and 40k is to be donated to charity (via donor advised fund). In the standard treatment form 1040 will show 85k RMDs added to other income to form AGI (adjusted gross income), then as long as total charity deductions stay below 30% of AGI, 40k to charity is included as an itemized deductions and subtracted off to form 'Taxable Income'. In other words taxable withdrawals combined with a large charity itemized deduction results in only the difference [45k = 85k - 40k] being taxed. If the 40k were to be given to charities via (multiple) charitable rollovers and a 45k withdrawal taken to meet the 85k RMD, then taxable income is up 45k in both cases. There is a difference in AGI, it is 40k higher in the standard treatment.

2nd order advantages

Forbes points to some 2nd order advantages. Because the charitable rollover keeps AGI down, Medicare premiums which are AGI triggered, might be lower. The biggest advantage I can see is a charitable IRA rollover is it provides some investment flexibility. Rather than just funding charity donations through appreciated securities (via donor advised fund) money can come from any IRA investment (like high yield bonds and RE).

Not a huge advantage, but if this is right it would save 525 dollars in MA taxes for every 10k transferred from IRA to charity to meet the IRA required minimum withdrawal.

---------------------------------

(update

12/12/11) Another extension of the over age 70 1/2, 100k 'IRA charitable

rollover' was included in financial crises legislation extending it through

Dec 31, 2011, where again it is scheduled to sunset. But note an important

caveat is that the IRA charitable rollover cannot go to (or through) a

'donor advised fund'!

The charitable IRA rollover provision has been extended for 2010 and 2011, allowing those over age 70 1/2 to make tax-free distributions of up to $100,000 from their IRAs directly to qualified charities. It is important to note that donor-advised funds, private foundations, and supporting organizations do not qualify to receive tax-free distributions from IRAs. (Fidelity)(update 6/6/10) Unfortunately the 'IRA charitable rollover' (the nice IRA tax avoidance loophole described below) has expired. It existed for four years (2006 to 2009). It was extended in 2007, but expired at the end of 2009.

IRS Publication 590 (2009), Individual Retirement Arrangements (IRAs), "Qualified charitable distributions are scheduled to expire and will not be available for 2010"While I read there is some sentiment in Congress for bringing back the it back, I suspect that the governments need for revenue will prevent it. Slott is a little more optimistic, "An extenders bill drafted late last year includes the extension of the QCD, and it is still expected that this will pass. Of course, almost all pundits also agreed that there was no way the estate tax would disappear in 2010!" (posting on his IRA Help forum, May 2010)

search terms: qualified charitable distribution

(QCD), IRA charitable rollover

-------------------------------

Pension Protection Act of 2006 allows people over 70.5 to transfer (rollover)

up to 100k annually from an IRA while living to charity (starts

2006, expires Dec 2007(update --- extended through 2009 by bailout

bill), to a max of 100k/yr). These charity deduction withdrawals are not

taxed

and contribute to meeting the minimum IRA distribution requirements.

It's an alternative to making a withdrawal, paying taxes on the withdrawal and taking a charity income tax deduction. From a tax viewpoint this new direct IRA to charity transfer is cleaner. Ideally if you take an IRA withdrawal and then give the money to charity, you can avoid paying taxes on that money because you get a charity deduction on your income tax which equals the amount of your taxable withdrawal. The problem is that there are a lot of traps with charity deductions:

* you must itemize deductions

* charity deductions are capped at (30% to?) 50% of adjusted gross income

* charity deductions and are phased out at high incomes (roughly 150k)

* Massachusetts (and some other states) provide no tax breaks for charitable

giving

because they do not allow itemized deductions. (In MA direct IRA

to charity is 5-6% tax saving)

* adjusted gross income above 25k-44k range cause SS payments to be taxed

With direct IRA to charity transfer all of the above limits (traps) are avoided . It makes larger charity gifts (while alive) more attractive (from Wall St Journal 12/11/06). Here is a discussion of all this in an academic paper.

http://www.ncpg.org/gov_relations/Hoyt-CHARITABLE%20IRA%20ROLLOVER%20(revised).pdf

(Update 1/29/07) Charities says this method of give has proven popular (Harvard reports 150 of these gifts in 2006). Not surprisingly charities are lobbying to make this IRA direct to charity rollover permanent.

Charity contribution from IRA advantages

(update

10/08) Charity giving from an IRA can reduce your minimum IRA withdrawal

and 1040 'adjusted gross income'. Example, your IRA minimum withdrawal

is 12k, but you want to give 10k to charity. If money goes direct from

IRA to charity it counts against you minimum withdrawal, so you only need

withdraw 2k from IRA, and only 2k will be added go gross income on your

income tax form.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------

PBS estate

planning guru (Ed Slott) on minimizing IRA taxes at death (3/08)

(see below)

At fund raising

time PBS has on lots of self-promoting speaker/gurus, and today's off the

wall talk was on the horror of IRA taxes at death (true) and what you can

do to minimize it. For what it's worth here briefly were his three points

(I have not checked any of this, so it's probably only half right, and

be prepared for lots of complications, restrictions and gotchas.)

Slott has a useful online IRA

Help forum where he posts.

1) Use the insurance exemption --- He recommended that you take millions

out of

your IRA now and use money to buy life insurance. On TV he says the insurance

money is tax free (and not included in the estate). (One reason he gives

is

to use the insurance to pay estate taxes if you don't have enough non-IRA

money to pay them.) Another way to Rothify your IRA?

2) Married people should not make their spouse their IRA beneficiary.

The issue

is the threshold in the estate tax and how get as much money as possible

under the threshold to minimize (high) estate taxes. He says each person

gets an estate tax exception of 2M (it changes every year), so a couple

can

get a 4M exception, but not if spouses leave their estates

to each other.

Blowing a 2M exception is big bucks.

3) Stretch IRA --- Make your child or grandchild a beneficiary

on your IRA, then

most of IRA taxes can be postponed for decades. When the IRA is inherited

the required minimum distribution (which is taxable) is reduced to 2-4%

per

year based on the life expectancy of the younger beneficiary. As long as

the

investment returns exceed the required minimum payout the IRA can continue

grow.

Ed Slott

When I heard

the PBS IRA pitch again, I found out the IRA pitchman is named Ed Slott.

While he is definitely a showman, it turns out he is a CPA and a legitimate

expert on IRA's. I've noticed recently that the regular Retirement column

in the Wall Street Journal uses him as an expert for IRA questions. I'm

reading his book now, Parlay Your IRA into a Family Fortune. While

it has showman aspects to it, there's also a lot of good IRA information

in this book that I have not seen anywhere else, and more importantly what

seems like good advice on minimizing IRA taxes.

Stretch IRA

While Slott

(badly) oversells the 'IRA stretch' concept, it does appear to be a valuable

technique for reducing IRA taxes in the case where IRA funds at death are

to be inherited by younger members of the family. It requires that an IRA

be properly set up and properly handled by the beneficiaries. The trick

is that younger beneficiaries are able to reduce the required minimum payout

of the IRA to 2% to 4% a year because of their much longer expected lifetimes.

This can allow the IRA to grow for decades more after death of the owner,

and by delaying the payment of most of the IRA taxes until decades after

death it can greatly reduce the effective tax the beneficiaries

have to pay on the inherited IRA money.

My Amazon review of Ed Slott's book

Here is my

July 2008 review of Ed Slott's 2005 book -- Parlay

Your IRA into a Family Fortune. Review Title: Good IRA Reference, but

Stretch IRA Wildly Overhyped

"This is both a very good and very bad book. Slott is a CPA and his bio indicates that he specializes in IRA law and estate planning. The retirement column in the Wall St. Journal uses him as an IRA expert. If you've seen Slott on PBS, you know he is also a pitchman and showman. This book is a mixture of expert IRA info and advice and wild overselling.--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------On the plus side:

This book is full of IRA information and good IRA advice presented in a very readable manner. I made dozens of notes in the front cover while reading this book. An excellent IRA reference. And I think the book does a service by pointing out that the IRA code has (sort of) a loophole that allows the 'effective' taxes paid on the IRA to be greatly reduced if the IRA is passed on to younger family members who should (Slott recommends) only take out the minimum annually over their lifetimes. Slott calls this the 'stretch' IRA.On the negative side:

Your IRA can grow into a FAMILY FORTUNE, he screams, with pages of tables showing a 100 thousand IRA growing to millions (in one case to nearly 300 million if left to grow into well into the 21 century!). Nonsense, what about the time value of money? Slott never heard of it (or pretends he never heard of it). The reality, of course, is that if your income tax rate is, say, 33% then when you withdraw IRA funds you lose 1/3rd of it to taxes. The best that even a perfect tax strategy can do is recover this 1/3rd. Nice, but hardly a fortune.Slott provides a useful check list of features an IRA contract should have. You would think that maybe he would read the IRA contracts of top IRA providers (like Fidelity, Vanguard) and tell us how they stack up? Nope, that's our job, not his.

Convert to a Roth IRA and your money will grow TAX FREE he screams. Slott's very positive on Roth IRA's, too positive. I worked through a Roth conversion example and find that the extra shielding that a Roth IRA allows can boost your after-tax returns a little. (Calculation details are in 'Roth Primer' section of the 'Charity' essay on my home page.) I calculate in a 6% market environment that Roth IRA will yield 6% vs an after tax yield for a traditional IRA of approx 5.4%, or an extra 0.6%/yr investment gain. However, there can be a serious downside to doing a Roth conversion that Slott doesn't mention. A large Roth conversion will likely be taxed at a much higher incremental income tax rate than normal minimum withdrawals, and since Roth has only a tiny yield advantage over a traditional IRA it could easily take a decade or more just to get even."

There are other assets besides IRA that have 'designated beneficiaries'. The general rule appears to be if an asset has a 'designated beneficiary' it bypasses the will and probate. Assets of this type are life insurance, 403(b) accounts (Vanguard has a 403(b) beneficiary form). I also recently have seen that non-shielded accounts (at least at Vanguard) can have beneficiaries (see below), but not sure if works the same as with IRA beneficiaries.

Do not think that you have named an IRA beneficiary simply because you have executed a will. IRAs should not pass through your will. If they do pass through the will, not only are they subject to probate costs, but also the (potentially) big advantage to your beneficiaries of continuing the tax shielding of your IRA for their lifetime (stretch IRA) is lost. An IRA should pass (directly) to the person(s) named as your IRA beneficiary. IRA beneficiaries are the person(s) listed on IRA beneficiary forms provided by the IRA custodian (mutual fund or bank holding the IRA). If you neglect to name an IRA beneficiary, or your IRA custodian (or beneficiaries) cannot locate your IRA beneficiary form, then your IRA will most likely pass to your estate and be probated according to the terms in your will.

Who holds IRA beneficiary form?If your IRA does pass to your estate, then it will be distributed according to your will if you have a will. That means that your IRA which should be a non-probate asset, will now become subject to probate and the related legal complications.

Obviously an important issue is recording and storing the IRA beneficiary election. I do not see any agreement in IRA references on this point. With a will there is little doubt that the owner keeps it. But an IRA has a custodian (like Fidelity or Vanguard) and they have the money!I have read the small print in the Fidelity IRA Custodian and IRA beneficiary forms. Fidelity says sign the form and send it to them. They make no mention of copies. The Fidelity's IRA forms read like Fidelity is (simply) going to send the IRA money to whoever's name is on the IRA beneficiary form that they have in their files. I suspect legally it's not this simple. Another problem, of course, is that the custodian over decades can lose an IRA form. Ed Slott says this happens all too often! (I can certainly see this happening, say, when a small bank is bought and records need to be transferred.)

The following questions come to mind about the IRA beneficiary form:

* Should you sign only one form or multiple copies?

* Who keeps the original(s), and who should have copies? Custodian, owner,

beneficiaries?

* Is a xerox copy valid?

* Is it a good idea to give beneficiaries a copy?

* What happens if a more recent signed IRA beneficiary form is found in

your records at death, or in possession of a beneficiary, than the copy

on file at the IRA custodian?

* What if multiple signed forms have the same date and disagree, what then?

An IRA owner's estate is the worst possible choice as IRA beneficiary, but becomes the default when IRA owners do not name a beneficiary. Naming a beneficiary is easy to do, and if not done much of the value of an IRA at death can be lost to taxes and costs.

One IRA 'expert' recommends

** Name your IRA

beneficiary now and keep an acknowledged copy - signed and dated by someone

of authority (anyone with a title) at your IRA financial institution -

of your IRA beneficiary designation form.

Also name a secondary (or contingent) beneficiary in case your primary beneficiary predeceases you or to create an estate planning path. Let your heirs know where the form is. If they cannot find it and your financial institution has changed, merged or has simply lost the form, then you have no designated beneficiary.

Beneficiaries

for non-shielded accounts (7/08)

Reading about

IRA's on the Vanguard diehards forum on Morningstar I saw that quite a

few posters said they also had beneficiaries on their non-shielded (taxable)

accounts. New to me. This appears to be the Transfer on Death (TOD)

plan (formerly called the Vanguard 'Directed Beneficiary Plan'). I read

elsewhere that a general way for an asset to not pass through probate is

by contractual arrangement. I guessing that this Vanguard plan works this

way, that it some sort of a contract you enter into. Does Fidelity have

something similar? I need to research this.

I see Vanguard forms include:

(Vanguard) Transfer on Death (TOD) Plan Kit

This

is a 12 page document that appears to describe the plan. It's identified

as, "For nonretirement accounts: Use this kit to designate or change

your Vanguard® nonretirement account beneficiaries (not to be used

for annuity contracts)."

Here is an excerpt from the above document. It certainly looks like it works similar to an IRA beneficiary form. It states clearly that the purpose of 'this plan' (whatever that may include) it to bypass probate, and it supersedes the will.

(see material on this topic at the end)

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

A Primer on Roth

IRA conversions (6/08) (added 20 years numbers 1/22/13)

IRA gurus

(like Ed Slott) and IRA references often just say a Roth IRA is good thing

with advantages over a traditional IRA, but don't explain. A general rule

in reducing taxes is always pay them later. That's why tax shielded

accounts like 401(k) and IRA make sense. With these accounts you can delay

paying your taxes for decades, and due to the time value of money,

your real (or effective) tax rate can be greatly reduced. {(1.05)^30 =

4.3 and (1.06)^30 = 5.7 which means that delaying the payment of taxes

for 30 years effectively cuts the real tax you pay by about a factor

of 5}

But Roth IRA's are counterintuitive, because with a Roth IRA you pay your taxes up front. OK after this the money grows tax free, but why taken together is this a good thing? I've thought this through and here is how to look at a Roth conversion

Assume:

Traditional IRA (no further contributions)

100k, 6 % earning, 33% income taxes (fed + state),

20% cap gains taxes (fed + state)

Question:

What is the advantage (if any) in doing a Roth conversion?

Conclusion

#1

* A Roth conversion saves no money at all on the IRA principal

Why is there no gain on the principal?

In a traditional

IRA your account in 'n' years multiplies by (1.06)^n, then at payout you

get to keep 67% of it with the remaining 33% going to pay (income) taxes.

If you do a Roth IRA conversion and pay the income taxes that come due

(on the amount converted) by taking it out of the IRA (important!),

then your initial account principal is reduced to 67% of what it was. (This

is a little tricky and technical, I am making some assumptions here.) It

then grows (tax free) over n years by (1.06)^n.

But multiplication is commutative, it doesn't matter whether you multiply by (1.06)^n first, then 0.67 (as in a traditional IRA) or the other way around by 0.67 first, then (1.06)^n (as in a Roth IRA). The result is the same. Your after-tax money is your original IRA account value x (1.06)^n x 0.67.

From another point of view while you don't gain anything on the principal by doing a Roth conversion you don't lose anything either. So even though you have paid all those taxes when you do the conversion you have in a sense totally preserved the shielding the Traditional IRA was giving you. Plus there is the benefit that you can now shift some additional funds from being taxable to being shielded. It is the shielding of this added (outside) money, which is used to pay the income taxes triggered by the Roth conversion, that increases the return of the IRA account from 90% of market return, pre-conversion, to 100% of market return, post-conversion.

Psychic loss?

A Roth conversion

can appear to reduce your net worth, since your (total) accounts are now

smaller due to all those taxes you paid. It can be argued this is (sort

of) a psychic loss. The reality, of course, is that you only

really owned 67% of your Traditional IRA, so whether you pay the conversion

taxes from the IRA or with outside money, a Roth conversion does not

affect your net worth.

So why would anyone want to do a Roth conversion?

The reason

is that if you have non-shielded (taxable) money available to pay

the income tax that a Roth conversions triggers, you are able (in effect)

to shield the earnings on this money from all future taxes (at least

that's the deal the US tax laws offer now, who knows about the future).

In our example of a 100k Roth conversion the funds used to pay taxes that

will be shielded from future taxation is 33% x 100k = 33k.

Aside --- Am I eligible to Roth Convert?So how good a deal is a Roth conversion? Well it depends (somewhat) on whether the funds used to pay the conversion taxes come from 'fixed income' funds or 'equity' funds.

I recently learned that as long as your income is less than 100k, you can Roth convert a million dollar IRA (or any size IRA), because the amount you IRA Roth convert does not figure in your eligibility to convert. (I learned this from Ed Stott's book and have confirmed it from other sources.)

a) Using fixed income funds

Taxes must

be paid annually on fixed income (like MM or bonds) earning. So in our

example 33% of the 6% return (2% of balance) is lost each year to taxes,

giving us an after-tax return of 4%.

taxable

(1.04)^10 x 33k = 48.85k

(1.04)^20 x 33k = 72.3k

Roth

(1.06)^10 x 33k = 59.1k

(1.06)^20 x 33k = 105.8k

-------------------

--------------------

Difference 10.25k

Difference 33.5k

(Roth advantage over 10 years)

(Roth advantage over 20 years)

b) Using equity funds

I assume here

that a 6% equity (nominal) return can be separated into [4% capital gain

+ 2% dividend] with taxes delayed until sold on the capital gains but paid

annually on the dividends.

If the funds used to pay the Roth triggered income taxes are taken from equity, say from index funds, the saving are less than with fixed income funds. The reason is that taxes on equity funds are lower than fixed income funds, because, one, (most) capital gains taxes are delayed until the shares are sold, and two, capital gains taxes (at least now) are less than unearned income rates. In other words there is already some degree of lower taxes and tax shielding in funds invested in equity in taxable accounts.

(minor update --- I was using 33% for the tax on equity dividends but this is too high, since under Bush the tax on so-called 'qualified' dividends was substantially reduced. Below I've assumed the tax on equity dividends are down from 33% to 20% = (15% fed for 'qualified' dividents + 5% state).

Let's assume the equity is held ten years and then sold, and that 2% per year dividends were paid by the equity on which taxes had to be paid annually. So 20% of the 2% dividend (0.40% of balance) is lost each year to taxes, resulting in the account growing each year by 5.60%. So in 10 years our 33k grows to (56.9k = (1.056)^10 x 33k) and, then its sold and capital gains taxes need to be paid on the gain. Let's assume capital gains tax is 15% Fed and 5% State for a total of 20%. (And let's adjust the cost basis from 33k to 35k to account for the continuous reinvestment of dividends at higher prices.)

taxable

56.9k - 0.20 x (56.9k - 35k) = 52.5k

98.1k - 0.20 x (98.1k - 38k) = 86.1k

Roth

(1.06)^10 x 33k = 59.1k

(1.06)^20 x 33k = 105.8k

-------------------

---------------------

Difference 6.6k

19.7k

(Roth advantage over 10 years)

(Roth advantage over 20 years)

Conclusion

#2

* The saving in taxes by shielding an extra 33k (when taxes are paid with

outside taxable funds) results in a Roth conversion increasing after tax

value of the 33k after ten year by 6.6k to 10k. (20k to 33k after 20 years)

Summary

Here are the

after tax totals for a (Traditional 100k IRA + growth of 33k in a

taxable account), and a 100k Roth account in 10 years (with 33k added at

conversion to keep the total at 100k). Note the 33k if in equity grows

at the rate of 5.60% (after taxes are paid on dividends) to 56.9k in ten

years, then cap gains (@ 20%) must be paid on the growth in the account.

If invested in fixed investments, it grows at 4% to 48.85k.

Traditional

0.67 x (1.06)^10 x 100k = 120.0k

33k growth (taxable)

+ 48.85k (fixed) or 52.5k (equity)

-------------------------------

total 168.85 to 172.5k (or 170.7k for a conservative

portfolio

50% fixed and 50% equity)

Roth

(1.06)^10 x 100k = 179.1k

(+8.4k advantage)

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

(update --- numbers for 20 years)

Traditional

0.67 x (1.06)^20 x 100k = 214.9k

33k growth (taxable)

+ 72.3k (fixed) or 86.1k (equity)

-------------------------------

total 287.2 to 301k (or 294.1k for a conservative

portfolio

50% fixed and 50% equity)

Roth

(1.06)^20 x 100k = 320.7k

(+26.6k advantage)

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

In a 6% investment

environment a Roth conversion allows you to capture 6%, which is all

the market return, so your 100k Roth account grows in ten years to 179.1k,

all after-tax. In comparison a Traditional IRA (100k face value, but real

worth 67k) + 33k in taxable funds) grows in ten years at a slightly lower

effective

rate of 5.55% ((1.055)^10 x 100k = 170.8k), which reduces the after-tax

total to about 171k. So a conversion of 100k account to a Roth (best case)

would increase account totals over Traditional IRA results over ten years

about 8k = (179k - 171k) or 4.5% more spendable cash, and over 20 years

about 27k = (321k - 294k) or 9.2% more spendable cash.

'Best case' caveatRoth advantage

An important caveat is that the above analysis ignores extra cost that can easily be incurred when doing a Roth conversion. The problem is that the amount converted in a year is added to your adjustable gross income for that year and can easily for a moderate to large size conversion push you into a higher incremental tax bracket. For example, an increase in effective tax rate from 25% to 33% (or 33% to 39%) on each 100k converted can nearly wipe out the 'Roth advantage' (8k per 100k) for its first decade.

However, compounding does cause the Roth advantage to grow with time, as can be seen by comparing the 20 year to 10 year numbers. The Roth dollar advantage over a traditional IRA at 20 years is roughly x3 what it is at 10 years.

Simple view

You have an

IRA and taxable funds to pay the income taxes that will come due (immediately)

when doing a conversion. So why Roth convert? Here's a very simple answer.

Conversion is basically a wash to the funds in your IRA (see caveat below) due to the 'multiplication is commutative' rule. But the return of the (formerly) taxable funds increases from less than market rate (due to tax costs) to market rate, because its (future) gains are no longer taxed.

Market perspective

A market perspective

is a useful way to look at the effect of doing an IRA Roth conversion.

After a Roth conversion going forward you start capturing 100% of

market return, obviously very desirable. Whereas over a ten year period

a Traditional IRA captures about 90% of market return (5.49% vs 6%). The

poorest performer is a unshielded fixed income account, which after paying

annual taxes, delivers only about 67% of market return.

Charity perspective

From a charity

perspective a Roth IRA conversion is a disaster. If you plan to

leave the funds in a Traditional IRA to charity, then there is no way

you want to Roth convert and pay all those taxes. The charity pays no taxes,

so all the money you give to the government now to pay income taxes would

end up in the hands of the charity. The 5% better investment gain of a

Roth (after 10 years) pales beside the 33% of principal lost to taxes when

it was Roth converted.

Comparison of Shielding Options

It's interesting

to compare all shielding options by extending our 10 year example (above).

Again we start with 100k (after-tax equivalent) and a total return of 6%

a year for 10 years. Same 33% income taxes and 20% capital gains taxes.

Note in the case of a Traditional IRA the starting amount is a 100k IRA

+ 33k non-IRA. The reason for this is that at 33% income tax rates you

really only own 67% of the 100K Traditional IRA. (We will continue to make

the simplifying assumption that the total return on fixed income and equity

are the same.) Here is the after-tax money you end up with after ten years

starting with 100k:

Taxable account

(fixed)

100k x (1.04)^10

= 148.0k

(equity)

100k x (1.054)^10 - 11.85k (cap gain) = 157.4k

100k Traditional IRA + 33k taxable

(see calculation above)

= 168.85k (fixed)

= 171.6k (equity)

(100k Traditional IRA + 33k taxable) converted

to 100k Roth IRA

100k x (1.06)^10 = 179.1k

The interesting result is that a Roth IRA does come out the best. In ten years it provides about 5% more than a Traditional IRA, 13.8% more than an unshielded equity account, and 21% more than an unshielded fixed income account. Roughly double these percentages for twenty years.

Roth complications and caveats!!

* Big negative

---

High

tax rates on a big conversion

In our contrived

example the income tax rates are fixed (33%), but I in the real world a

big Roth conversion (say 1/3 million) could very easily increase state

and fed marginal tax rates the year of the conversion by 10% or so (say,

33% to 43%). If this is true, this is a loss of 10k on every 100k converted!

This is going to take a long., long..... time (about 15 years) to get back

because the gain of a 100k Roth conversion is only 660 dollars/yr (= 33k

x 5% gain x 0.33% tax). This is a big negative to doing Roth conversions.

It means Roth conversions can only be done a little at a time so as to

not bump up incremental tax rate, but since Roth conversions have only

a small gain, then the overall gain becomes very small.

Incremental

tax rates (single, 2008)

32k - 78k 25%

78k - 164k 28%

164k - 358k 33%

358k +

35%

* Another hidden tax of a big Roth conversion is that Medicare rates will go up 1k or so that year because you are rich!

* Big positive

--- Reduced estate size

It appear

that 'face value' of IRA's are used in figuring estate taxes, and estate

tax rates can be huge like 45%. So a big plus to a Roth conversion (even

if paying high incremental tax rates) can be that the Roth conversion substantially

reduces the (apparent) size of the estate. In our example a Roth conversion

combines a 100K Traditional IRA and 33k taxable cash into a 100k Roth.

Notes from an estate point of view every 100k IRA converted 'magically'

makes 33k in taxable assets disappear from the estate.

Of course,

you really only owned 67% of that 100k traditional IRA, but apparently

the estate tax people don't care about that and they hit your estate with

a tax on a tax using the face value of your IRA. So here a Roth conversion

can provides a big saving, almost half of the 33k (14.85k = 0.45 x 33k)

that would have gone to estate taxes is saved from the tax man.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

Information

below is raw info about giving to charity gathered from many sites online

in pretty much random order.... It's preliminary and needs to be confirmed.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

Taxes on IRA distributions

In MA if you made any after-tax contributions to IRA's they come out first

(tax free).

-- "IRA distributions are not taxable until all of your contributions that

were previously subject to MA (income) taxes are recovered." (MA Dept of

Revenue, 2008)

IRA distributions tips

Minimum required

distributions do not need to interfere with investment stategy. According

to WSJ's retirement column (12/08) mutual funds can simply be transferred

(without sale) from an IRA to a taxable account to meet IRA minimum distribution

requirements.

Standard

IRA vs Roth IRA Overview

(IRA info for my nephew, Jan 2012, setting up an IRA

account with 10k initial contribution)

I didn't think to mention this, but you need to delay doing your taxes until the IRA is set up. The reason (as I explain below) is that contributions to a standard IRA reduces your taxable income, so this should you save you quite a bit in taxes. If your tax bracket is 25%, then a 5k IRA contribution before April 15 for 2011 should reduce your 2011 taxes by [0.25 x 5k] = $1,250, and then the 2nd 5k would reduce your 2012 income taxes next year by the same amount. In other words opening up, or contributing to, a standard (not Roth) IRA with 10k, should reduce your taxes by about 2,500 over the next two years. This is one thing people like about tax shielding. You do not get a tax reduction if the money goes into a Roth IRA. The Roth IRA tax advantages come 40 years from now.

Don

When are taxes paid

The big difference between the two IRA types is when you pay taxes: standard IRA is when you take money out, normally in retirement. In a Roth IRA you pay taxes up front when you put money in. A standard IRA reduces your 'adjusted gross income' by the amount of an IRA contribution. It's not an itemized deduction, better it's an adjustment to income, so you don't need to itemized deductions to get the tax savings. If you earned say 60k in 2011, the your 5k standard IRA contribution for 2011 is subtracted off (there is an IRA line on the 1040 form), so you are taxed as though you earned 55k. If you are in, say, the 25% income tax bracket, this should reduce your income taxes by 25% x 5k = 1,250. with a similar reduction in taxes in 2012 from the 2nd half of the initial 10k.

Same multiplier

Here's the math on why it doesn't make much (or any) difference paying your taxes now (Roth IRA) or 40 years later (standard IRA). The correct way to figure gains of the market is by (a series of) multipliers, one for each year. If the market goes up 10%, the multiplier is x1.1, down 10% it's x0.9. For money invested for many years you stack up the multipliers: 1.1 x 1.05, x .84 etc, hopefully totally to a significant multiplier. For example 5% earned over 40 years is (1.05)^40 = 7.

Now here is the kicker and why there is basically no difference in tax savings between the two types of IRAs. We start with an assumption: 'tax rates 40 years from now will be the same as now'. Obviously no one knows what taxes will be 40 years, but this is a reasonable starting point. What you really are interested in when investing for retirement is how much 'spendable' money you will end up with. Let's say taxes are 30%. In both IRA's the market gains need to multiplied by a tax multiplier, which is x0.7, since you get to keep 70% of the market gain. When you look at the final gain equations (with tax multiplier) for the two types of IRAs, they are the same! In our simple model it makes no difference if you pay your IRA taxes up front (Roth IRA) or at the end (standard IRA) you end up with exactly the same amount of spendable money.

Working some numbers

This may seem counterintuitive, I mean don't you end up paying much more tax dollars with a standard IRA? Ans yes, but it doesn't matter. For example, say you put in 5k pre-tax dollars every year into a standard IRA, and in retirement your IRA statement says you have one million dollars. With taxes at 30% the way to think of this is you have 700k spendable money and uncle Sam gets the other 300k. Now let's look at a Roth IRA. You had the same 5k of pre-tax saving to invest, but after you pay your 30% (income) taxes on the 5k you have only 3.5k to put into the Roth IRA. Every input is reduced by 30%, so in retirement your Roth IRA statement will say 700K, all of which is spendable. No difference.

With Roth a little more can be shieldedTips for Reducing Your Estate

The above example also shows what advantage the Roth IRA has in some cases. With both types of IRAs the contribution limit is 5k/year (at your age). In our example with Roth the 5k pre-tax was reduced to 3.5k due to the taxes owed, but if you had saved 7.14k, you could have paid your 30% tax and put the remaining post-tax 5k [7.14 x .7 = 5.0] into the IRA. In other words the main advantage of a Roth IRA is that if you are saving a lot it effectively allows you to shield about 30% more money per year than a standard IRA. Whether this is a significant advantage or not depends on how much you save and and other tax shielded plans you may have, most of which have a lot higher contribution limit. In my view the tax advantages of the two types of IRAs are not that different. Another consideration is that in future years you always have the option to convert (with some limits) a standard IRA to a Roth IRA by paying the taxes. You can't convert a Roth IRA to a standard IRA (nor would you want to since you have already paid your taxes.)

(TIAA) Transfers to tax-exempt institutions or charitable trusts can be made free of gift or estate taxes during your lifetime or at death.

The advantage of insurance (as I understand it), aside from providing liquidity to pay estate taxes, is that funds transferred to insurance can with manipulation (taking advantage of a 'loop hole') be excluded from your estate, thus avoiding estate taxes. (see Insurance as synthetic Roth IRA below)

Susie Orman

on keeping life insurance money out of your estate --- If you own

an

insurance policy on yourself and die, the money goes into your estate.

There are two ways to keep the life insurance money out of your estate

when you are the insured:

a) set up an Insurance Trust to own the policy with your childen

as beneficiaries of the trust

b) your children own the policy and are the beneficiaries

This offshore site (http://www.sovereignsociety.com) recommends reducing your estate with offshore Trusts, Family foundations, variable annuities, life insurance.

Charity

donations at death reduce taxable estate (4/15)

It's

been tricky to find hard information as to whether charitable contributions

reduce the value of your taxable estate (for fed estate tax purposes).

Briefly it's a two step process. One, the IRS makes it clear that all your

property, including face value of shielded accounts (even if they avoid

probate via beneficiary), determines the value the gross account.

Two, the value of the taxable estate is determined by subtracting off from

the gross estate the following:

26 U.S. Code § 2055 - Transfers for public, charitable, and religious uses

U.S. Code › Title 26 › Subtitle B › Chapter 11 › Subchapter A › Part IV › § 2055

For purposes of the tax imposed by section 2001, the value of the taxable estate shall be determined by deducting from the value of the gross estate the amount of all bequests, legacies, devises, or transfers—Above from 'Cornell Law School, Legal Information Institute' pretty clearly says to determine the amount of your fed taxable estate subtract off the value of charitable transfers at death from the gross estate. Wikipedia is consisten, saying:(2) to or for the use of any corporation organized and operated exclusively for religious, charitable, scientific, literary, or educational purposes, including the encouragement of art, or to foster national or international amateur sports competition (but only if no part of its activities involve the provision of athletic facilities or equipment), and the prevention of cruelty to children or animals, no part of the net earnings of which inures to the benefit of any private stockholder or individual, which is not disqualified for tax exemption under section 501 (c)(3) by reason of attempting to influence legislation, and which does not participate in, or intervene in (including the publishing or distributing of statements), any political campaign on behalf of (or in opposition to) any candidate for public office;

(https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/26/2055)

Once the value of the "gross estate" is determined, the law provides for various "deductions" (in Part IV of Subchapter A of Chapter 11 of Subtitle B of the Internal Revenue Code) in arriving at the value of the "taxable estate." Deductions include but are not limited to" Certain charitable contributions;[21] (It was Wikipedia link 21 that led me to the Cornell Law reference above.)-----------------------------------

-- Like the examples above, life insurance is often a large portion of a person's estate. However, the average person is unaware that life insurance proceeds are usually includable in the insured's estate. To avoid estate taxes on life insurance the policy must not

1) name the

estate as a beneficiary and

2) the deceased

must not possess "incidents of ownership" at the time of death. In other

words the deceased must not have had any of the following powers at the

time of death: a) right to change beneficiaries; b) right to assign the

policy; c) right to cancel the policy; or d) the right pledge or borrow

against the policy.

-- A life insurance trust is the most effective means of assuring that the proceeds of a life insurance policy are not included in your taxable estate and it is moderately simple to implement. The average costs of drafting and implementing a life insurance trust is around $950. When you compare the cost of the life insurance premiums and the fact that up to 55% of the insurance proceeds will be paid to the IRS and not to intended beneficiaries, it often makes economic sense to implement a life insurance trust.

Comment

on life insurance tax avoidance risk

It appears

to me that use of life insurance as a tax avoidance procedure has a risk

that I rarely (if ever) see commented on. Obviously money paid to an insurance

company for life insurance company doesn't come back until your dead. And

techniques to keep it out of your estate require you before your death

to basically give away the rights to this money.

Giving away the money in advance

It seems to

me this tax avoidance procedure only makes sense for excess funds

that you are positive you will never need to tap during your lifetime.

You better be dam sure you won't ever need that 1M you're planning to use

to buy life insurance, because once you pay the premium that money is gone,

it's just been given to your heirs. Essentially it's a rich man's procedure.

Slott is doing it because he's probably rich, but as usual he doesn't explain

that what may apply to him may be totally inappropriate for you.

The only way

(I see) to mimize this risk is to buy the insurance late, late (ideally

just before your death). So a key question is how many years in advance

does a strategy like this need to be implemented. Can you buy life insurance

to get the tax benefits at age 90? Does the law require the insurance to

be in place for a period before your death? Is this law stable or continually

changing? All these issues would need to be researched.

-----------------------------------------

Insurance => Synthetic Roth IRA

One estate

planning site (motto: 'Advanced Life Insurance & Annuity Strategies')

pushes insurance as a substitute for a Roth IRA, calling the plan a 'synthetic

Roth IRA'. Insurance and Roth IRA are basically similar in the sense that

you pay taxes now on invested funds, and then they grow and can

be withdrawn tax free. As I understand it, the claimed advantage of the

synthetic Roth IRA over a real IRA is:

Advantage

* Insurance

(with planning, see above) can be excluded from estate whereas a

Roth IRA is included. As I understand this may make sense when the

amount involved is over the estate tax exemption and will be taxed at estate

tax rates. To make this concrete say 2M is withdrawn, taxes paid (at highest

incremental tax rates!) and used to buy (what I assume is the equivalent

of 2M) in life insurance. Obviously with estate tax rates in the 50% range

pulling 2M out of the estate looks like it could potentially offer a 1M

tax saving, obviously a huge advantage. Whereas if an IRA is Rothified,

the same income taxes would be paid now, but the amount would still

be in the estate and (it is assumed) subject to estate taxes.

Disadvantages

* Life insurance

is usually a high cost investment, which is very bad over a lot

of years. And even worse in many ways the insurance companies makes it

their business to hide the costs, so you don't really know what you are

paying. (This pro-insurance site even says that if you aren't under

age 60 and in good heath, the synthetic Roth IRA is not attractive because

the insurance costs will be too high!!)

* Complications with trusts or beneficiary owing the insurance to keep it out of the estate. This, of course, is the 'loop hole' that makes insurance attractive. Another site warns, "The family member should pay the premiums from his/her own checking account. The IRS will examine thoroughly and will tax any insurance if it is not properly set up."

* To me it is very suspicious that there is a lot of vagueness about what type of life insurance to buy. Apparently Slott (who is always positive about insurance) apparently doesn't give any recommendation! The synthetic Roth site describes the insurance as (I quote) "a particular type of cash value life insurance product". (well that's clear)

* It

is an insurance product, which means there is a real cost for this feature,

and (very likely) at least with some of the money you are betting with

the

insurance company on how long you live, and one of you can lose.

-----------------------------------

Charity

Options for Qualified assets --- At death

* IRA, 401(b), or any qualified asset to charity at death

via listing

charity as account beneficiary

-- (easy) just need to list charity (with IRS #?) in the account

as beneficiary

-- very (100%) tax efficient

-- normally whoever receives qualified assets has to pay the

deferred income tax on all the assets at their

incremental income tax rate. Charities don't pay this tax.

Charity gets 100% of value of asset.

-- assets distributed in this way are not included in my estate

so huge estate tax on the asset is avoided.

-- reduces size of estate (potentially reducing estate

tax on other assets)

-- (TIAA) you can name a trust as beneficiary of your

retirement plan assets if you don't annuitize

Charity

Options for Qualified assets --- Living

(TIAA) For

gifts during your lifetime, you can take an income-tax deduction for each

year a gift was made of up to 50 percent of your adjusted gross income.

(pretty useless, also AMT probably can wipe this out)

* "Donor Advised Fund" also called 'Charitable Gift Fund',

'Public charity with a donar-advised fund program'

-- Charity gets 100% of value of asset

-- I get tax deduction

-- Flexibility as to how funds are distributed to charity

-- Vanguard and Fidelity have this type of plan

-- (TIAA) Pooled Income Fund

--- income goes to donor as income stream for life

--- donor receives an income tax deduction

upon initial contribution

-- at death capital goes to charitable beneficiary

-- (TIAA) Charitable Gift Annuity

--- contract between a person and a charity. In

exchange for an irrevocable gift the

charity agrees to pay the donor a fixed

sum each year for life.

Seems like difference between Pooled Income fund and Charitable Gift Annuity is who controls the principal. In the former its donor and in latter its charity.

Estate Tax

Rules -- Federal

(TIAA) In 2002, federal tax rates on estates above $1 million start at

41 percent and rise to 50 percent for estates above $2.5 million.

(TIAA) Unified Credit on Estate and Gift Taxes --- This is a federal credit that reduces the tax generally due on your taxable estate after your death or on taxable gifts made during your lifetime. The amount of assets you can pass on free of federal gift or estate taxes by using your unified credit is called the applicable exclusion amount. In 2002 and 2003, that amount is $1 million. When you use your unified credit to offset gift taxes, you reduce the amount available to offset estate tax

For federal estate-tax purposes, your estate includes your home, cars, retirement accounts, taxable investment accounts, life insurance, collectibles and so forth.

You might want to leave just enough to charity to reduce your taxable estate to the magic $2 million figure should you die in 2006 to 2008.

To reduce your taxable estate. Assets passing from retirement plans to qualified nonprofit organizations like Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, Inc. are entirely removed from your taxable estate. This can potentially save your estate thousands of dollars in taxes. If you are considering making gifts to nonprofit organizations as well as to your heirs, you would be wise to give retirement plan assets to charity and other investments to your heirs.

Outright Gift --- If you want whatever remains in your retirement account to pass to Lincoln Center, Inc. at your death, simply ask the plan administrator for the appropriate form needed to do this. You then indicate how you wish the remainder to be distributed. If you do name Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, Inc. as a beneficiary, please send us a copy of the form. We will keep in with our records.

Estate Tax exemption

1.5 mil 2005

2.0 mil 2006

3.5 mil 2009

infinity 2010 (no estate tax)

1.0 mil 2011 (revision to 2001 value)

Incremental Estate tax

(above exception)

46% 2006

45% 2007 - 2009

55% 2011

Gift tax threshold

12k (2009)

Unified (gift & estate)

tax credit

345,800 (2008)

Cost Basis Step Up

inherit -- yes

gifted -- no (do not gift appreciated assets)

Loop

hole to reduce capital gains tax and pass more wealth to heirs (2/10/13)

-- COUNTRIES

like Canada have a tax on asset appreciation, based on the value of the

assets at the time of the owner’s death. The United States does not, and

the tax code contains a huge loophole through which to pass wealth to one’s

heirs. Here is how that can work in practice:

-- A billionaire can borrow against his stocks, art and real estate, and spend that borrowed money without paying tax. All he has to do is pay interest on the loan. When he dies, his heirs can sell the assets to pay off the debt. Under an existing rule known as the “step-up in basis,” no matter how much the assets have appreciated in value, no one will owe income tax on that gain. And the rest of his fortune goes to his heirs without anyone ever paying income taxes on the appreciation in the assets. (NYT 2/10/13)

Not sure I see how this works.... OK, I think I see it....

Normally in retirement you need to sell off your assets to live. Say over time you sell half your assets, this cuts the value of your estate in half and triggers a continuing tax (capital gain tax) on assets sold, which would be 10% of the money received for assets with 50% cost basis (20% capital gain tax). The article is suggesting don't sell your assets borrow against them. Over time you borrowed the full value of half your asset. This gives you the same money to live on, but here the continuing cost is the loan interest cost. The loan interest is on all the money received, which in today's market might be 5%? Sure the loan must be paid off by heirs at death, but they received twice the assets than they otherwise would have, so when they pay off the loan they have left the same amount as assets they normally would have received.

The way to look at this I guess is as a capital gains tax reducer. Say you sell 100k with x2 or x3 appreciation. At 25% capital gains (fed + state) the tax is 12.5k for x2 and 16.7k for x3. If loan rate is 5%, then loan cost is 5k, so annual (tax) saving of 7.5k to 11.7k. The 'flaw' (weakness) in this tax avoidance scheme it seems to me is that only works for money spent, presumably a tiny fraction of a billionaire's wealth. If he borrows more and saves it as cash it just goes into his estate to be tax at estate rates. If he buys yaughts and planes, they have a high cost basis, so they just go into the estate too. (am I missing something....)

Gift Tax

Once you have passed the unified credit exemption limit, giving gifts makes

even more sense because the effective tax rate on gifts is lower than on

an estate. Gift tax is calculated like a sales tax; the amount of the gift

is multiplied by the tax. Estate taxes, however, are levied on the entire

estate, including the money you send the IRS to pay those very estate taxes.

Unified Credit --- 345,800 (2008)

While in principal

there is an gift tax to be paid (by the giver) if the gift to (each) person

is over 12k/year, in practice (i.e unless the gift is huge) the tax is

zero.

The gift tax is integrated with the estate tax and there's something called the "unified credit" which is nearly 1/3 million dollars. Until this amount is exceeded the tax due will be zero, however, you are supposed to file a form with the IRS (Form 709) about the gift so they can can track it. A gift above 12k affects the value of your estate, which of course only matters if your estate is big enough to be taxable, and it's paid when your dead.

Here are IRS links on the gift tax. The 2nd link has an example showing how the Unified Credit works to cancel the gift tax.

http://www.irs.gov/publications/p950/ar02.html#d0e368

http://www.irs.gov/publications/p950/ar02.html#d0e347

-----------------------------------

More on Gift Taxes --- Exceeding the 12k 'Limit' (3/15/11)

A 3 min Google yields below,

which lays out the hidden assumptions of the gift tax 'limit'...

The key sentence below is this: "The rules let you give a substantial amount during your lifetime without ever paying a gift tax. As of 2008 the amount is $1,000,000." It also says, The person receiving a gift never pays a tax regardless of how large the gift. A gift is not income.

Notice the double talk below. It ends up recommending keeping below 12k after just explaining that this limit is (in most cases) no big deal, just an IRS reporting limit, essentially a bookeeping entry that might (might!) increase estate tax when you die. Everyone's situation is different, so tax advisors tend to give conservative (in my view over-simplified) guidance that it's best to stay below 12k/yr.

Clearly the main

purpose of the law is to prevent people from giving away their money prior

to death to avoid estate taxes, but if your estate is (moderately) below

the estate tax threshold and will not be subject to estate taxes, the 12k

limit is not a real limit. It's just a threshold above which you need to

do a little figuring, and isn't that why you have an accountant!

-------------------------

Giving more than the annual (12k) exclusion amount

--If you give

more than the annual exclusion amount to one person in a single year you'll

have to file a gift tax return. But you still won't have to pay gift tax

unless you gave given a very large amount. The rules let you give a substantial

amount during your lifetime without ever paying a gift tax. As of 2008

the amount is $1,000,000.

-- You don't use up any of this amount until your gifts to one person in one year exceed the annual exclusion amount. For example, if you make a $14,000 gift in 2008, you have used up only $2,000 of your lifetime limit.

-- Any amount you use out of your lifetime gift tax exclusion counts against the estate tax exclusion, which is $2,000,000 as of 2008 and $3,500,000 as of 2009. This means that if you use $250,000 of the limit by making gifts during your lifetime, you have reduced by $250,000 the amount that can pass through your estate free of the estate tax. So you shouldn't ignore your lifetime limit even if you feel certain that your lifetime gifts will never add up to that amount. It pays to plan your gifts around the annual exclusion amount and the exclusions for educational and medical expenses wherever possible.

http://www.fairmark.com/begin/gifts.htm

-----------------------

A family accountant was

asked to comment. His response is consistent with above and updates the

numbers. He reports the direct gift tax limit is now much higher (5M) and

the annual reporting threshold a little higher (13k), but the scaling back

of estate tax threshold by large gifts, which I suspect may be the most

important consideration, he didn't mention.

-- There is no tax consequence to the recipient of a gift, it come to them tax free. The donor must file a gift tax return for any gifts to any one individual who is given more than $13,000 during a calendar year. The donor has a lifetime maximum of $5,000,000 before they have to pay a tax on gifts to individuals.Mass Estate Tax Rules -- Mass

Will

Reflect carefully on what you want your will to accomplish and put your

thoughts into writing. Then call an attorney to draft the document for

you. A will always should be prepared by an attorney to be certain it conforms

with federal and state regulations.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Gifts of Retirement Assets

Careful planning for the disposition of retirement plan assets—IRAs, 401(k) plans, 403b plans, and other qualified pension or profit-sharing plans—can help to avoid undesirable tax costs. In certain situations, gifts to Wharton of retirement account balances can improve the donor's overall tax consequences, increase the amounts passing to heirs and reduce income and estate taxes.

Retirement assets can be subject to multiple levels of taxation. The combination of federal income, estate and excise taxes can seriously erode the value of retirement savings.

First, as a rule, retirement savings are subject to federal income tax as the funds are distributed to the beneficiary(ies).

Second, the law requires that certain minimum distributions be made from retirement accounts after the individual attains age 70 and 1/2. Failure to take the required amount results in a 50% penalty tax on the undistributed amount.

Third, at death, any remaining retirement account balance is included in the calculation of the gross estate. Consequently, retirement savings can also increase federal estate taxes. A generation-skipping tax may also apply to substantial account balances that pass to grandchildren or to other remote generations.

Finally, after death, payments made from retirement accounts to the designated beneficiaries will be taxed as received by them at ordinary income tax rates.

Thus, the overall tax rate assessed on passing retirement assets to your heirs can exceed 75%!

Rather than

lose the bulk of these retirement assets in taxes, some Wharton donors

elect to give these assets directly to the School, while using other, less-taxable

assets to pass on to their children and other beneficiaries. To do so,

a donor makes Wharton the beneficiary of each retirement plan he or she

wishes to gift to the School.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Another

advantage to making a cash gift is that it is deductible against up to

50 percent of the donor's Adjusted Gross Income.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Five Tax-Saving Principles

Principle No. 2

"Giving while

you're living" is a tax-wise idea. The reason is the income tax deduction—both

federal and state. Charitable gifts made during your lifetime provide an

income tax deduction not available through a bequest gift. Because the

outright current gift is no longer includable in your estate, these gifts

ultimately avoid estate taxes as well.

Principle No. 3

Giving assets

is better than giving cash, especially long-term, highly appreciated assets.

This

is because of the dual tax benefit of an income tax deduction based upon

the fair market value of the gift plus the added benefit of avoiding the

capital gains tax.

Principle No. 4

Planned giving

(i.e. charitable remainder trusts; charitable gift annuities) provides

three powerful benefits. It provides significant income tax and estate

tax benefits and provides a lifetime income stream as well as a significant

remainder gift to charity. Life income plans offer you the opportunity

to make a current commitment to charity, receive a lifetime income stream

for you and your spouse, avoid an immediate capital gains tax on a gift

of appreciated property, receive an income tax deduction for a percentage

for the total amount gifted and remove the asset from your estate which

may provide significant estate tax savings.

Principle No. 5

Don't forget

about your pension plan as a giving opportunity. "Income in respect of

decedent" assets such as pension plans, IRAs and other qualified plans

generally provide better tax benefits in a testamentary gift. The best

type of asset to gift to charity through an estate will normally be an

asset that produces taxable income. Most assets that an heir inherits are

free from income tax. However, with the exception of a surviving spouse,

an heir will pay income tax on amounts received from a decedents' retirement

plan.

If you are going to make a charitable bequest, it is usually better

to transfer assets subject to income tax to charity and transfer non-taxable

assets to heirs.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Bequests

Bequests are

gifts made by will. They are the most popular type of planned gift and

have been crucial to the extraordinary growth and success of The Museum

of Modern Art. Whether you wish to provide general operating income or

to support a specific department or program at the Museum, your bequest

expresses your lasting commitment to MoMA. A bequest to the Museum may

also help you meet your financial and estate-planning goals, since an estate

and gift tax charitable deduction for the entire amount of the gift is

allowed. While your estate plan will be prepared by your attorney in consultation

with your tax and financial advisors, the Museum's Office of Planned Giving

would be pleased to discuss any of the various giving opportunities with

you.

Types of bequests include:

* A cash bequest of a specified dollar

amount.